A Guest Blog Post for University Press Week

A parson tucked away in the tiny village of Ousby who formulates an evidence-free theory of the evolution of the earth.

A forgotten poet who imagines that the citizens of Saturn enjoy a marvelous overhead view of planetary rings.

A nutritionist whose dietary recommendations give clients so much energy that they exercise themselves to extinction.

Along with many other unusual persons granted a second life in university press books, these eighteenth-century thinkers could be generously styled creative, but they might also, more accurately, be deemed wrong. Such eccentric if occasionally entertaining earners of that off-putting adjective, incorrect, epitomize the many real and fictional figures who missed the mark while showing a bit of creativity. Whether bad leaders who erred their way to their destinations, such as HMS Bounty Commander William Bligh; whether “tech” inventors who max out at 98% accuracy, such as those who struggled to make an accurate clock for use in maritime navigation; or whether make-believe heroines like Samuel Richardson’s Pamela, who never seems to know what is happening to her yet who ends up as lady of the manor, the erroneous outnumber the accurate in studies of the past.

Aided and abetted by an assortment of university presses, I have spent most of my professional life in (sometimes) creative commentary on the vast corpus of early modern errors. A life spent in nonstop discussion of ideas that stand no chance of being true might qualify as “creative” in the worst sense: a diddling away of a tiny bit of talent on miscellaneous curiosities. In this peculiar diversion of educational resources, I am far from alone. By the brutally pragmatic standards of twenty-first century industry, the vast majority of what university presses publish must count as little more than a distraction from the pursuit of productivity. The prognosis is not much better for those actively creating the cultural history of our own era. Given the proliferation of discredited ideas in the middle ages, the Renaissance, and the Enlightenment, we may infer that most of our notions will eventually end up among quaint collectibles, like old farm equipment nailed to the walls of a Cracker Barrel restaurant.

Creative thinking—figuring out the meaning of our history or artfully understanding the culture of yesteryear or discovering something in the past that has unexpected applications in the present or future—is largely about the sympathetic stewardship of error: the willingness to cut some slack to the past and to appreciate what even crackpots (perhaps inadvertently) achieved. After all, mainstream figures like astronomers William and Caroline Herschel can seem freakish, what with sitting out, night after night, a brother and sister team looking at luminous smudges about whose true nature they have nary a clue. In the effort to appreciate the productive irregularities of the past, university presses make a colossal contribution. At 250 pages and under the imprimatur of a legitimizing institution, a university press book provides the perfect vehicle in which to observe not only one or two historically significant mistakes but to view manageable arrays of discarded phenomena or ideas—to reveal worthwhile patterns amidst a bevy of blunders. The significance of the university press book as a genre expressing creative curatorial concern for the variably valuable paraphernalia of the past is easy to overlook. A comparison between the compact modern university press book and an intelligent but unwieldy commercial synoptic production such as Will and Ariel Durant’s Story of Civilization will immediately show the amazing ability of the university press format to extract an abundance of knowledge from unusual topics.

When not studying the peculiarities of the long eighteenth century, I spent a certain amount of career time—over a decade—in “faculty” or “shared” university governance, dealing with the astounding range of people, activities, and administrative arrangements in a multi-campus public university. This experience repeatedly showed the centrality of university presses for whatever remains of creativity in modern mega-universities. By persisting in the protection of impracticalities, university presses keep their sponsor institutions honest, open, and, in a word, creative. Reliably and consistently attracting media attention, university presses remind everyone that higher education really should be about innovative thought rather than about sport, grants, and state legislatures. Throughout my years in university governance, I never ceased to be amazed at the reluctance among powerful administrators, when budget cuts came along, to withdraw even the slightest bit of support from a costly press that would never turn a profit. Such, to make an odd comparison, is the power that religious symbols exert over Dracula. Books that gleefully celebrate knowledge without concern for gain dazzle every eye and sear through resistance. They surprise even the skeptical with their sacramental power. The more peculiar, offbeat, and creative the volume, the stronger the enchantment. Paying heed, in a university press book, to all those historical figures who made creative mistakes thus brings us happily back to the true, energetically creative purpose of universities.

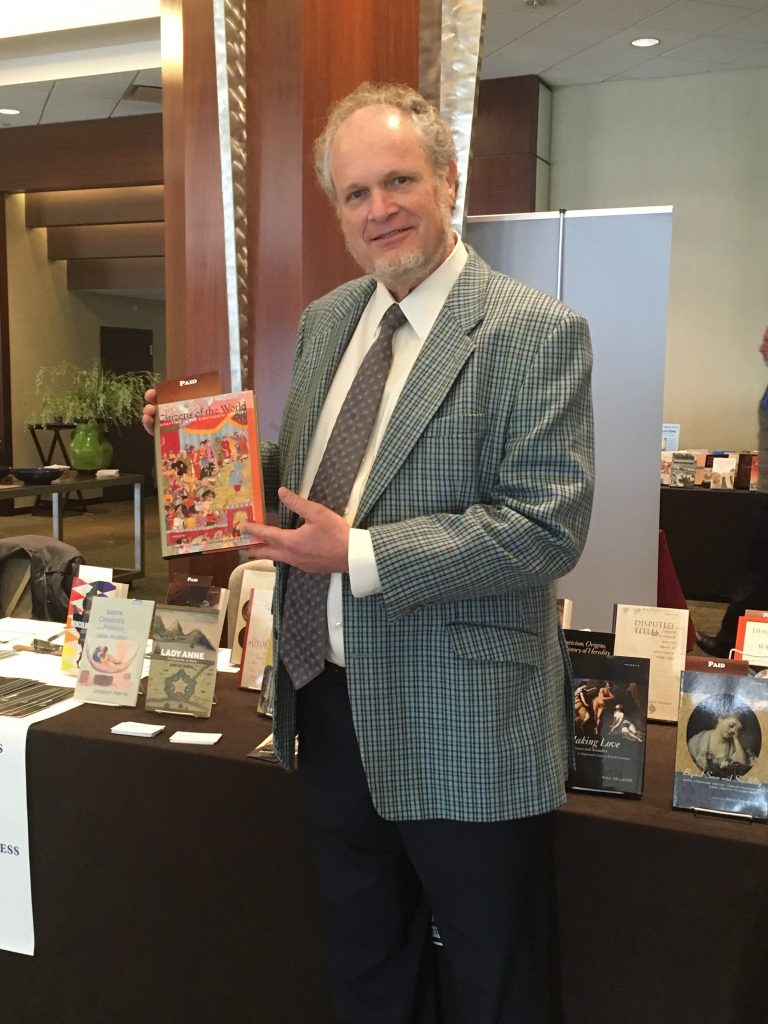

Kevin L. Cope is Adams Professor of English Literature at Louisiana State University. He is the author or editor of dozens of books and articles, including Hemispheres and Stratospheres: The Idea and Experience of Distance in the International Enlightenment and, with Cedric Reverand, Paper, Ink, and Achievement: Gabriel Hornstein and the Revival of Eighteenth-Century Scholarship. He is also the founder and editor of the annual journal 1650-1850: Ideas, Aesthetics, and Inquiries in the Early Modern Era. A former member of the National Governing Council of the American Society for University Professors, Cope is regularly referenced in publications such as The Chronicle of Higher Education and Inside Higher Ed and is a frequent guest on radio and television news and talk shows.