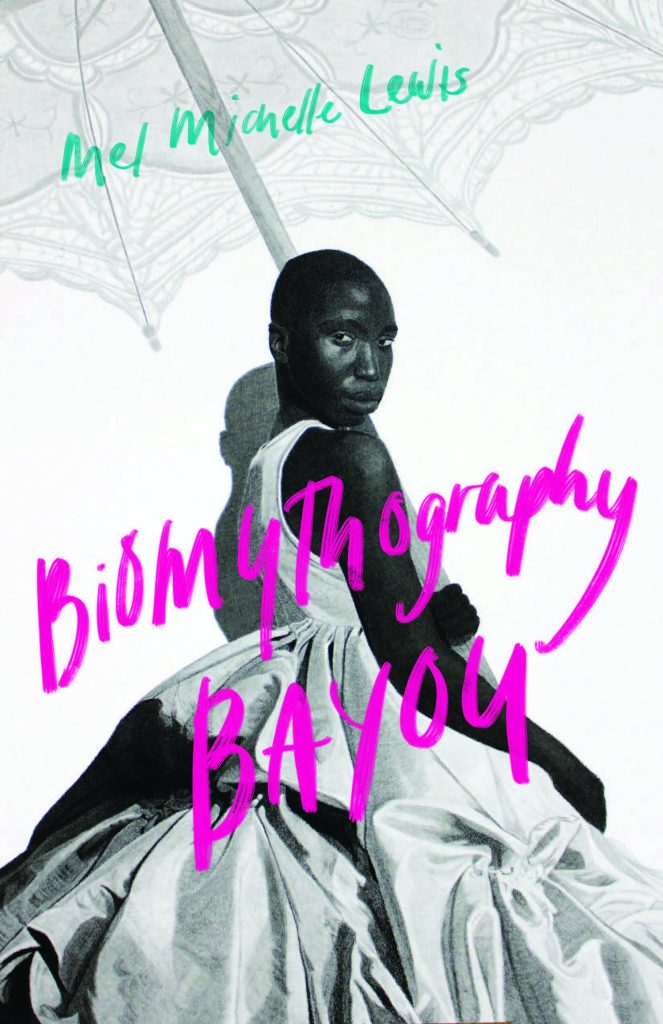

Biomythography Bayou is more than just a book of memoir; it is a ritual for conjuring queer embodied knowledges and decolonial perspectives. Blending a rich gumbo of genres—from ingredients such as praise songs, folk tales, recipes, incantations, and invocations—it also includes a multimedia component, with “bayou tableau” images and audio recording links. Inspired by such writers as Audre Lorde, Zora Neale Hurston, and Octavia Butler, Mel Michelle Lewis draws from the well of her ancestors in order to chart a course toward healing Afrofutures. Showcasing the nature, folklore, dialect, foodways, music, and art of the Gulf’s coastal communities, Lewis finds poetic ways to celebrate their power and wisdom.

Here, we chat with Mel Michelle Lewis about their memoir, the process of writing, and their hopes for its impact.

BUP: To begin, what attracted you to the Griot Project Book Series? Why did you want to work with the Griot Project on Biomythography Bayou?

Lewis: I was thrilled to send Biomythography Bayou to the Griot Project. The Griot Institute’s focus on Black life and culture, and the Press’ devotion to the interdisciplinary exploration of the aesthetic, artistic, and cultural production of the Diaspora attracted me. I also needed my intersectional approach to Black queer narratives to be well supported. I wanted to work with a press with an interdisciplinary focus that would welcome the prose, poetry, praise songs, recipes, spells, invocations, and visual art in the text.

Lewis (cont.): I am also so grateful for the legacy of Dr. Carmen Gillespie and am honored to connect with her generous spirit as a part of the Griot Project Book Series family.

BUP: There is an undeniable embodiment of the stories you tell that is perhaps due to the various forms the writing takes throughout; what were you hoping to depict through the physicality of Biomythography Bayou?

Lewis: Biomythography Bayou is a performative text, the embodied text of Black life and culture was critical to share through what I would describe as literary corporeality. I am heavily influenced by Gwendolyn Brooks’ poetic portraiture, Audre Lorde’s erotic verse, and Zora Neale Hurston’s embodied knowledge. I write with the senses and physical body as a corporeal presence on the page as a point of entry for the reader, hoping they will feel and experience more than words. I want the reader to feel, “feel Honeyman’s sound climbing round in their ribs hive” when he hums, and the taste of Asberry’s “Paste of c o o l r e d c l a y.”

BUP: Your memoir is notably multi-modal, including sections of verse, prose, recipes, photography, and even audio. How did you decide what portions of your book needed which medium? Did the content of the ideas determine what form it would take, or was there an intentionality behind the nature of how stories were included?

Lewis: All of the content told me how it wanted to be presented. A character like PyroBeau had a sound that needed to be expressed with a particular cadence, “ya see, for a small fee.” The Road Home needed a praise song for veneration. Lapine and Dauphine needed poetic storytelling to capture duality. The altars and their referenced elements needed to be seen and woven through the senses. Even the elemental essays revealed they wanted poems and invocations, even as I imagined them to be “scholarly” prose with citations. I truly did not know which or how many modes would be incorporated until the book was completed, I responded to the need of the story rather than pre-planning how it would be presented.

BUP: Focusing more closely on the photography included in your book, what about their subject matter made it impossible or ineffective to relate to the audience solely via text? What significance do you place on the inclusion of visual elements within a medium that is traditionally not based on physical images?

Lewis: I am so thrilled to have had the opportunity to include the color photos of altars as ritual images. Presenting these elements allowed me such intimacy with the reader. The images are a conjure portal; we follow Lil’mae and her cousins on their journey in the epic poem “What on Earth,” and the reader witnesses the peacock feathers and a quilt in reverent form. The stories of my grandmother are amplified by seeing a waterfall of handwritten recipes on her altar.

BUP: Although Biomythography Bayou is a memoir, there is a strong focus on community and collective memory and culture. What did you hope to capture and what sort of effect did you hope to cultivate?

Lewis: Yes, collective memory across generations and space/time is at the heart of this work. My intention was to cultivate community, share traditions, honor dialect and foodways, and present remembrance as a ritual. The Griot uses storytelling to carry tradition and culture through generations, this book is many hands working and many voices speaking through me.

BUP: Do you have any overarching questions or challenges you would like to pose to a reader of your book? something you would like them to ponder as they experience the memoir?

Lewis: I encourage readers to savor, to go slow, to open themselves to the Spirit of the book.

Biomythography Bayou is available to order here in paperback, hardback, and ebook.

Mel Michelle Lewis (she/they) is a multidisciplinary artist, writer, teacher, and environmental justice practitioner. Their creative work explores nature writing themes in rural coastal settings through the lens of Black, Creole, Afro-Indigenous, and queer embodied knowledges. Originally from Bayou La Batre on the Alabama Gulf Coast, they currently reside in Baltimore. Read more here: melmichellelewis.com

I found your article very well-structured and easy to read.