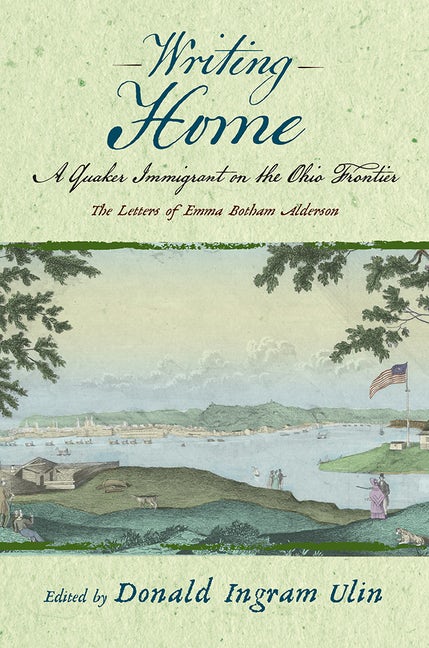

Donald Ulin, editor of Writing Home: A Quaker Immigrant on the Ohio Frontier, talks with our graduate assistant Madison Weaver about the challenges of archival work, Quaker views on social justice issues, and how the life of an ordinary nineteenth-century woman resonates with the contemporary immigrant experience.

Weaver: How did you find your way into the project of Writing Home?

Ulin: I grew up Quaker, attending a very liberal, unprogrammed Friends meeting, vaguely aware that there were other Quaker traditions, but not really thinking of them as real Quakers. In graduate school, my work on representations of the English countryside led me to William Howitt’s Rural Life of England (1837). From there I began learning about the Quaker couple William and Mary Howitt. As an American scholar of British literature, I became interested in Mary’s Our Cousins in Ohio, and was trying to put together an edition of that, since it’s been out of print since 1866. Then one day a Google search for “howitt” (just for the hell of it!) turned up a new page on the University of Nottingham’s website saying they had recently purchased a huge collection of Howitt correspondence—including letters from Mary’s sister Emma, the inspiration for Our Cousins in Ohio. I planned to include a few letters as an appendix to the book, but when I visited the Nottingham archive, decided that the letters deserved a publication of their own.

As I began to realize that Alderson and her family represented the more theologically conservative tradition that I had only ever heard of growing up, I had a kind of falling out with her and the project. As I persisted, however, I came to see the history of Quakerism, and perhaps religion and politics more broadly, in more inclusive and less binary terms.

Weaver: This sort of archival work seems a difficult and time-consuming undertaking. Could you tell us a bit about the processes of doing archival work in preparation for this book? Was there anything that surprised you in your research over the course of the project?

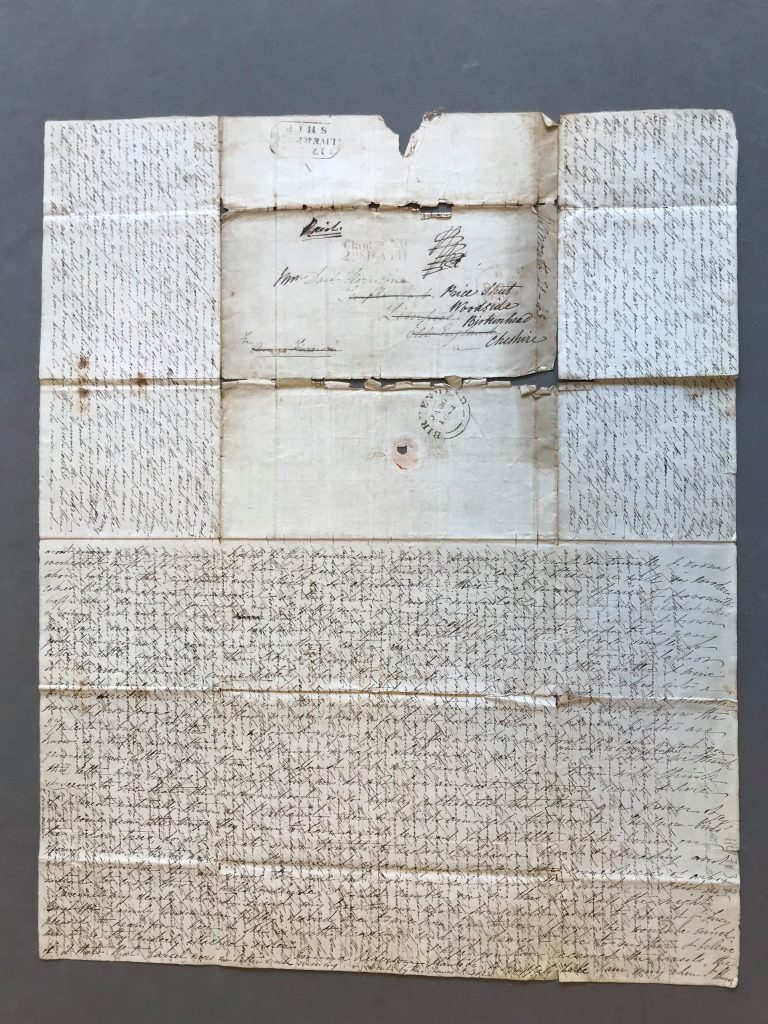

Ulin: There’s a tough balance to strike between thoroughness and efficiency. You want to collect every detail: paper size and type, watermarks, odd orthographic features, formatting, and so on. But there’s only so much time, so you have to define the parameters of the project and collect just what you’re going to need. Just reading the handwriting was challenging, but over time it became easier. Another challenge was the cross-writing—where the letter-writer finishes a page, rotates it 90 degrees, and then writes on top of what she has already written. I have included several images of these cross-written letters in the book. When I reached the letter in which Emma apologizes to her mother for the cross-writing and promises not to do it anymore, I breathed my own sigh of relief.

Weaver: Writing Home centers on the life of a Quaker immigrant on the American frontier. What can Emma Alderson’s writings illuminate about the immigrant experience in the nineteenth century, or perhaps even today?

Ulin: What’s particularly important about this work is that it brings to light the life of one particular immigrant, independent of any generalizations that we might make about “the immigrant experience.” That experience is different for every individual immigrant, which might be one of the most important truths to keep in mind in talking about immigrants from any period. Quaker immigrants in the nineteenth century had the benefit of an extensive support network of Quakers who had gone before. Through these networks, an immigrant was able to sustain some of her old national identity while finding her way into her new life as a productive member of this ever-changing country. In general, if not in specifics, this experience is no doubt shared by communities of immigrants in the United States today, be they Hispanic, Somalian, Rohingyan, or anything else.

Weaver: Part of what makes Emma Alderson’s story so engaging is how her letters are steeped in her Quaker views and experiences. Could you speak to how her Quaker beliefs might offer a unique perspective on the events of the time period?

Ulin: Quakers, Mennonites, and Church of the Brethren are recognized as the three “peace churches” for their absolute rejection of war. I don’t know so much about the other two, but the Quakers have also been well-represented in the ranks of those fighting for various social justice causes, including prison reform, abolition, and women’s rights. We can see these attitudes quite clearly when she writes about soldiers on their way to Mexico, freed slaves seeking to live their lives amidst terrible racism, and (to a lesser extent) the influential women in her own life. But Quakers were far from united in either their politics or their theology. The movements and controversies in American society around the war with Mexico, slavery and abolition, and the rise of evangelicalism are reflected in conflicts within the Society of Friends. Historians are familiar with the names of leading, public Friends who occupied one side or another of these conflicts—Joseph John Gurney, his sister Elizabeth Fry, John Wilbur, Levi Coffin of the underground railroad. What I think is unique about Alderson’s correspondence is what I can only call a more “ordinary” and personal perspective on this political and theological landscape.

Weaver: Emma Alderson’s writings seem to invoke fascinating intersectionality between her gender, class, religion, and nationality. How does this intersectionality speak to the uniqueness of her story? Is there a special moment in her letters or journals that has stuck with you?

Ulin: Very interesting question. It’s easy to generalize about women in nineteenth century America or Quaker women. They are either oppressed drudges or committed and articulate activists. Many (not all, of course) of the more activist women came from relatively privileged backgrounds, which gave them the education and liberty to pursue their work. As a middle-class, English-speaking white woman, Alderson occupied a privileged position on most counts. I’m not sure how clearly she recognized that fact, but the twenty-first century reader of her letters is always aware of the Black, or poor, or German-speaking others passing through the narrative, individuals both with whom and against whom she is constructing her own identity.

Weaver: Aside from Emma Alderson’s letters themselves, what other kinds of material are available in Writing Home? Why is the commentary and context so important in this sort of project?

Ulin: The book contains quite a few images of the actual letters, and I have also reproduced many non-textual elements, particularly the drawings and little sketches by Alderson or her son, William Charles. I have also included illustrations by Anna Mary Howitt for her mother’s Our Cousins in Ohio. These are interesting, not as illustrations of Alderson’s actual children, for indeed, two of the four illustrations depict incidents that did not actually occur, but for the ways in which Howitt’s book refigures those children for her own literary and ideological purposes.

The general introduction puts Alderson’s life and correspondence in historical context, with information about postal history, Quakerism, immigration, and more. In that introduction, I also situate this correspondence more theoretically in relation to recent scholarship on epistolarity, women’s writing, trans-Atlantic studies. The introductions to the three sections of the book provide historical and biographical background to the letters in those sections. The introduction to the third section provides the first detailed analysis of how these letters were transformed collectively by the two sisters into Our Cousins in Ohio.

A Directory of Names gives some information about most of the people named, including the pseudonyms assigned by Mary Howitt in Our Cousins in Ohio. So, a reader of Howitt’s book can quickly learn more about the real life of any of those characters.

Readers may also be interested in the epilogue, which follows the remarkable lives of the main characters and their descendants. One went on to found Bryn Mawr College, another set international legal precedents at the Nuremburg trials, another helped pave the way for the establishment of the Adirondack State Park.

A short appendix gives all of the physical attributes of the letters, including paper size, postmarks, and addressing.

Weaver: We live in a time when letter writing has fallen mostly out of practice, and the United States Postal Service faces serious risks of losing funding. How can Writing Home help us think differently about how we communicate, then and now?

Ulin: The materiality of the letter makes it an embodiment of, or a surrogate for, the distant sender. Time and again in these letters, Alderson reminds us of the power of a physical letter. In one letter she describes the pleasure of corresponding with her mother as a “pleasure of holding converse with thee.” Another time, thanking her mother for a parcel, she writes “it seems as if every thing was sanctified by thy touch; the very stiches on the wrappers are endeared to us.” Since working on this project, I’ve been trying to write more physical letters. It’s hard when you know that whatever news you are sharing will probably be broken in an e-mail or a phone call long before the other person gets the letter, but I know they still appreciate it when it arrives.

Donald Ingram Ulin is an associate professor and director of English at the University of Pittsburgh at Bradford. His new book Writing Home offers readers a firsthand account of the life of Emma Alderson (1806-1847), an otherwise unexceptional English immigrant on the Ohio frontier in mid-nineteenth century America, who documented the five years preceding her death with astonishing detail and insight.