A Guest Blog Post for University Press Week

“Sierra Leone, your tragedy was too painful to be a poem.

If you could speak, it would be raw in my bones!”

–Syl Cheney-Coker, “Lake Fire,” in Stone Child and Other Poems (2008)

My work in postwar settings has taught me that our moral indignation and empathic response to others’ pain sometimes recedes, and we grow numb, no longer capable of effective political action to prevent, oppose, or end injustice. Unlike sterile news reports, creative expression such as poetry can help us move past numbness and retain (or regain) a capacity to respond. After spending more than five years working as a psychologist and human rights advocate in international contexts, I was drawn to “found poetry,” a genre in which phrases from existing sources are presented in new ways. Found poetry is a vehicle for transforming seemingly indescribable events into literary expression, and powerfully impresses on the mind of the reader the voices of those affected.

I first encountered public transcripts from the UN-backed international war crimes tribunal in Sierra Leone in 2005, when serving as a psychologist for the trials held in Freetown. It became evident to me that eleven years of civil war had resulted in a new reality in which the unthinkable had become a part of daily life:

“…in Kono

when they chop off people’s hands

we use tobacco leaf

to tie it round the wounded place.”

The rebels who had tried to overthrow the Sierra Leonean government were eventually defeated, but the country suffered tremendous losses. The testimonies – comprising hundreds of witness reports – deserved the attention of the international community, but that attention was limited. A number of poets from the West African sub-region have tried to rectify that by creating poems pertaining to the war. Among these, the most notable are Liberian American Patricia Jabbeh Wesley, who has published several collections featuring poems about the two civil wars in neighboring Liberia, and Syl Cheney-Coker from Sierra Leone, whose 2008 collection contains compelling poems about the civil war in his homeland. Now, I have rendered the public transcripts into poetry to make a broader global community aware of the war’s impact and to underscore the twin truths of survivor suffering and resilience.

After I compiled this collection, I was faced with the task of identifying a publisher who would consider a book by a first-time author, the subject matter and genre of which were largely unfamiliar. I had a hunch that commercial publishers would not accept this book, but that a university press might. In spring 2019, I was blessed to contact Dr. Carmen R. Gillespie – poet, literary scholar, professor of English, founder and director of the Griot Institute for Africana Studies at Bucknell University, and editor of Griot Project Book series. She had a warm, encouraging attitude toward my proposal, and despite her sudden passing in August 2019, the book is now due out from Bucknell University Press in July 2021.

As I sit here today reflecting on the results of the U.S. presidential election, my mind and heart go back to the many Sierra Leonean women, men, and children whose limbs, lives, and voices were taken from them as a punishment for exercising their right to vote for a civilian government and their refusal to support a rebel force that tried to rob them of that right:

“Since you say you love a civil government

we are going to chop off your hands,

we will not let you go free.

If we don’t chop off your hands,

we’re going to kill you.”

After the war finally ended, Sierra Leoneans began the long, hard work of attempting to rebuild—and restore faith in—their society and country. That effort is ongoing in Sierra Leone as, indeed, it is in the United States and many other countries across the globe where rights have been violated and power abused. In August 2007, shortly before I left Freetown, millions of Sierra Leoneans all over the country braved long lines to vote in the first presidential election since the end of the long civil war. Those who had had one arm severed by the rebels voted with the other. Those who had been cruelly robbed of both arms voted with their toe-print. There is so much, so very much, that the world can learn from Sierra Leoneans’ determination to survive and to preserve or reclaim their dignity and human rights, including the right to vote and be counted.

University presses help make it possible to know about these stories, and to develop a keener alertness to the ways that language is used in public life: the kind of rhetoric that rationalizes aggression and the kind that serves to reduce it. If we strive to pay attention, we can discern truths that would otherwise slip away. Where do we locate the words to give voice to these truths? The words that we need might be anywhere. The words that we need might be everywhere. Listen. Read.

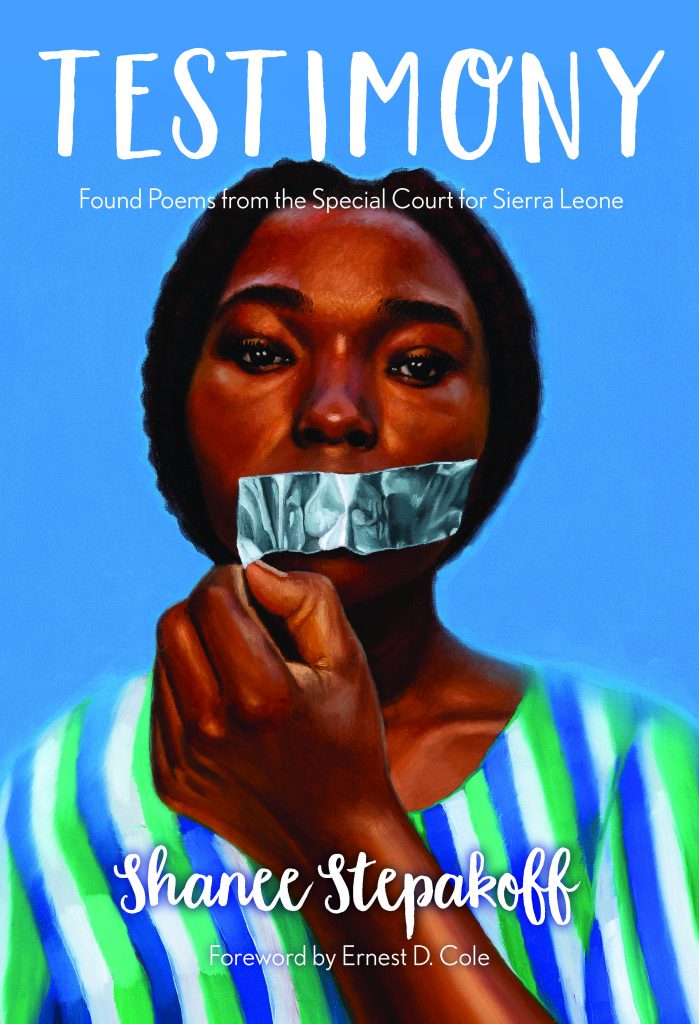

Shanee Stepakoff is a psychologist and human rights advocate whose research on the traumatic aftermath of war has appeared in such journals as Peace and Conflict and The International Journal of Transitional Justice. Her collection of found poetry, Testimony: Found Poems from the Special Court for Sierra Leone, is forthcoming from Bucknell University Press in June 2021.