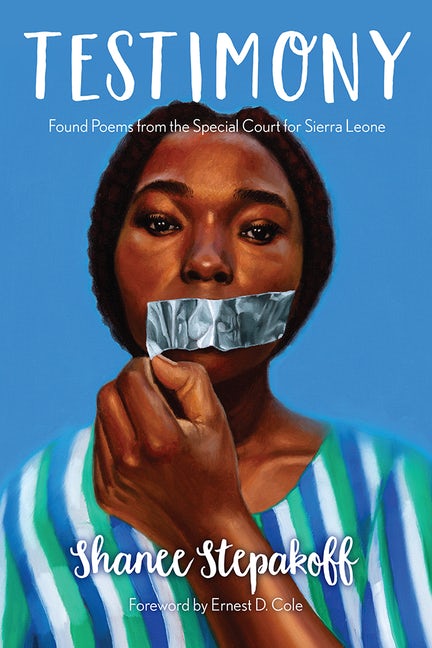

To wrap up National Poetry Month, we spoke with Bucknell author Shanee Stepakoff about poetry, publishing, and her forthcoming collection, Testimony: Found Poems from the Special Court for Sierra Leone. A remarkable collection of found poetry, Testimony is derived from public testimonies at a UN-backed war crimes tribunal in Freetown and aims to breathe new life into the records of Sierra Leone’s civil war, delicately extracting heartbreaking human stories from the morass of legal jargon. By rendering selected trial transcripts in poetic form, Stepakoff finds a novel way to communicate not only the suffering of Sierra Leone’s people, but also their courage, dignity, and resilience.

As a psychologist and human rights activist, why did you turn to poetry to tell the stories of Sierra Leone? What does the found poetry form offer this difficult work of sharing the testimonies of trauma survivors?

I had lived and worked in the region for several years and was aware that many truths about the civil war of 1991-2002 were not reaching an international audience because most readers from outside of the West African sub-region were not inclined to spend hours poring through lengthy books in subjects such as global history or political science.

I felt that a collection of poems would be a way to reach people who might otherwise not take an interest in the human impact of a war in a faraway country. In addition, the courtroom procedures and legal jargon that characterized the war crimes trials made it hard to hear the voices of the survivors who had come to testify. Distilling the lengthy trial transcripts into poetic form made it possible to listen to the narratives with greater attentiveness. I was also drawn to poetry as way to sort through my own vicarious traumatization. Of course, my effort to wrestle with the accounts of wartime atrocities was not nearly as arduous as those who were directly targeted, but nevertheless the process of composing poems provided me with a means of structuralizing reports that might otherwise have been overwhelming.

In the introduction to Testimony, you write that “The survivor must not merely speak but rather must address other people—specifically, those who are not only willing but determined to hear and to know. This is the broader, deeper meaning of testimony. To bear witness does not necessarily imply participating in a legal or juridical proceeding. To bear witness implies the existence of a speaker, a committed listener, and a language.” How might poetry help us become better, more committed listeners?

A poem is a form of expression that arises when a deep chord is struck within the literary artist and ordinary language no longer suffices. A new way of speaking was required, one with greater-than-usual potency. Readers sense that the poem arose from this deep place, and this piques their attention. A poem communicates about a human experience in a highly concentrated manner, thereby fostering recognition of previously-undiscerned realities. Poems tend to move people at the emotional level, not just the cognitive level. Usually a poem is more memorable than other literary genres, because a strong poem has precise phrases and images that leave an imprint in the mind of the reader. Poems can bypass the defenses that many people mobilize when confronted with evidence of human rights abuses because most poems have auditory and rhythmical properties that are paradoxically soothing even when the subject matter is painful. Literary devices such as assonance, alliteration, near-rhyme, and the right combinations of variation and repetition intensify our willingness to bear witness to harsh truths in a sustained manner without flinching.

Could you speak to the process of editing and publishing a first poetry collection?

I used a nontraditional approach, transforming prose transcripts into poetic structure, and the material was troubling in that it focused on a devastating war. Therefore, I was uncertain about whether any publisher would be open-minded enough to agree to even read the work, let alone commit to bringing it forth. I was extraordinarily lucky to have reached out to Carmen Gillespie, founding editor of the Griot Book Project Series, to ask if she would consider this collection. In 2019 she read some of the poems, then the manuscript, and committed to sending it out for review. She unexpectedly passed away amidst that process, and it seemed like the project might stall, but then Suzanne Guiod, editor-in-chief of Bucknell University Press, generously stepped in to carry it forward. I was given amazing support from a team of professionals, comprising Suzanne as well as two anonymous reviewers, Bucknell’s managing editor, the cover artist, the foreword writer, and later the copyeditor and production editors, with each person contributing their particular expertise. I am humbled and honored by their dedication and conscientiousness.

Who are other poets and writers you look to for inspiration or enjoyment? Who are you reading the most at the moment?

The “Further Resources” section in my book contains a list of writers from Sierra Leone and one from Liberia whose work highlights the wellsprings of creativity and resilience present in the region. For more than thirty years I have used poems in anti-racism training because they have a greater impact than any other genre. I’ve used Claudia Rankine’s 2014 collection, Citizen, which focuses on the insidious ways that anti-Black racism operates in day-to-day life in the US. I’ve also used a poem from Natasha Trethewey’s 2018 collection Monument, which portrays a childhood experience of racist terror. Yusuf Komunyakaa’s poems on the Vietnam War shed light on the legacy of war. Carolyn Forché’s 1981 collection The Country Between Us, about political repression and war in El Salvador, had a strong impact on me in my youth. More recently I read her 2019 memoir, What You Have Heard Is True, which explores the impact that her exposure to human rights abuses in El Salvador had on her writing. I am inspired by Brenda Hillman’s recent poems incorporating elements of found texts to give expression to grief and anger about militarism and hinting at possibilities for resistance. Aminatta Forna’s 2002 memoir, The Devil That Danced on the Water, tracing her search for the truth about the politically motivated execution of her dissident father by a corrupt dictatorial regime in Sierra Leone, and her four novels and forthcoming essay collection, inspire me not only because of her literary gifts but also because of her psychological and moral courage and her recognition that sometimes remembrance is the only redemption.

Shanee Stepakoff is a psychologist and human rights advocate whose research on the traumatic aftermath of war has appeared in such journals as Peace and Conflict and The International Journal of Transitional Justice. She holds an MFA from The New School and is completing a PhD in English at the University of Rhode Island.