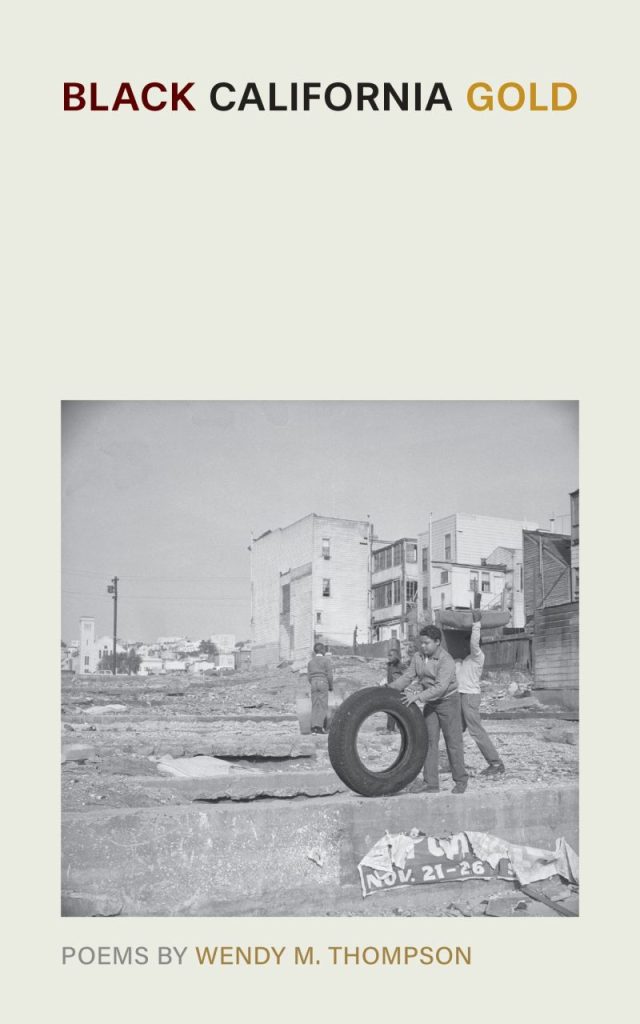

In celebration of National Poetry Month, we’ve invited Wendy M. Thompson to talk with us about her new poetry collection, Black California Gold. In this debut collection, Thompson traces the past and present of California’s Bay Area, exploring themes of family, migration, girlhood, and identity against a backdrop of urban redevelopment, advanced gentrification, and the erasure of Black communities.

These poems map a region where race, class, and language are just some of the fault lines that divide communities and produce periodic tremors of violence and resistance. While confronting assimilationist myths of the American Dream, Black California Gold also celebrates the Black residents of the Bay Area who have struggled to sustain home and hope amid increasingly inequitable conditions.

BUP: First and foremost, what made you seek out publication with the Griot Project? How do you see your work fitting into the conversation of African American studies?

Thompson: I wanted my first book of poetry to have a home with similar shelfmates. The Griot Project Book Series publishes both scholarly and creative projects that are heavily interdisciplinary and focused on the art, culture, histories, and contemporary realities of black America and the black diaspora world. That’s a wide expanse, and presents a large enough space for my own poetic meanderings which cover nature, the body, memory, grandparents, middle-class design and decor, wealth, food, death. All of these show up in some way in my work–both creative and scholarly–and actually speak to some of the exciting trends and directions in the field of African American Studies right now.

I also found out, after Black California Gold was published, that the series editor, Cymone Fourshey, and I share family origins and migration ties to Marin City, California. This made the Griot Project an even more meaningful placement as the home of my first book.

BUP: You discuss the languages in which you have lived your life through your familial connection. Do you feel poetry itself is another language? Who do you hope to speak to using it?

Thompson: Poetry is absolutely another language for me. It comes naturally and is an expressive form and device that I use on a daily basis beyond the written page. Just like black English, which in itself is poetic in form and syntax, poetry–the manipulation of words, line breaks, punctuation, imagery, metaphor, etc. to convey meaning–is my language. It’s the delicious way I get to play with sentences and ideas, from my mother’s stilted English to the specific flavor of black English that utilizes sarcasm and tone to amuse or cut a man down. How beautiful the moon is. How hungry my body feels. How deeply I adore or hate a person. It provides an exact way to see the world, to communicate what is experienced. I use it even when I’m not trying to use it: to abruptly cease, to tell a story, to conjure the dead.

As far as your question about the audience, I am always in conversation with other black folks. That is my audience. Folks from Oakland and elsewhere in the Bay Area–San Francisco, Richmond, Hayward, now in Stockton, Tracy, Antioch, Manteca, Sacramento. Folks who grew up with Southern grandparents, plastic covered furniture, one non-black parent, long hot summers of the 1980s and 1990s. Payphones, liquor stores, graffiti, sneakers hanging off the telephone line, poor man’s dinners with pork and beans on a paper plate, the most spectacular sunsets you’ve ever seen. My poetry is written for us, for a generation who grew up before this present cycle of displacement and gentrification, back when the Bay Area was still black. My poetry is also written for those who want to peek inside, to see what we were doing, how we were living in our neighborhoods, where we came from before things changed.

BUP: Continuing with the topic of language, there are several instances in which you include Chinese in the text of Black California Gold; how did you want the inclusion of these characters to operate within your poetry?

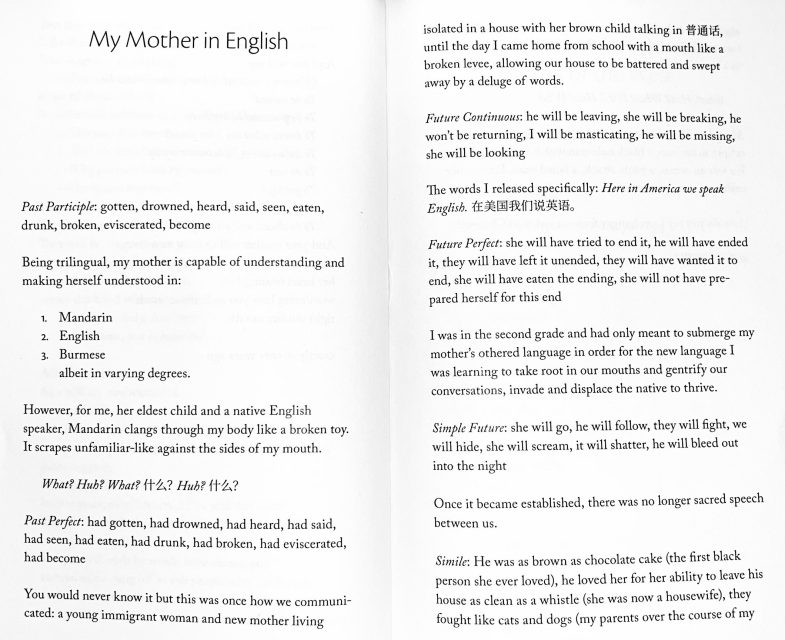

Thompson: Like I mention in my poem “My Mother in English,” Mandarin was the first language I shared with my mother. It was how we communicated: a young immigrant woman and her black mixed race child. But there would be a rupture when public education, and my own determination to learn English, would disrupt that intimate currency between us. This happened when I was in the second grade. That choice I made: To speak English. And to allow it to override Chinese as the dominant language. It really hurt my mother then, and I’ve held it as a loss between us ever since. I’m 44 now and I’ve begun incorporating Chinese into my creative work as a way to reclaim and acknowledge that foundation, that intimacy, and the rupture. I infuse it into my poems so it isn’t completely abandoned from my current narrative.

I also wanted to disrupt English as the standard and only language on the page for readers. That’s a definitive part of the California experience, or rather, the California reality: that English isn’t the standard and definitely isn’t the only. Being from here is to always see and read and hear and be around non-English words, phrases, speakers, and spaces. For black residents, there’s a denial and erasure in speaking and being heard in the Bay Area. This is the same region where black English has been denied public and institutional legitimacy and where the sounds, movements, foodways, religious practices, and cultural traditions of diverse Asian and Latino immigrant populations that came in the 1990s have become part of the daily norm. I wanted to include that, the feeling of having your everyday interrupted, turned on its head by this arrival, and the tensions around trying to understand it.

BUP: You paint a vivid and deeply personal picture of the Bay Area in California. Do you think poetry is able to better capture subjective experiences in a more accessible or representative way? What do you hope you were able to capture through the use of the medium?

Thompson: Poetry helps me paint a picture but it has its limitations. I can be a bit wordy and excessive and poetry requires me to be lean with my words. Don’t overexplain. Don’t stuff every definition and meaning into a sentence. Into a word! At the same time, poetry provides that attention to detail. It is literally fixated on the smallest aspect: a shape, a sound, a color tone, a gesture, a feeling. So the composition and color of the houses on the hillside in San Francisco in the poem “San Francisco (an ode to Harlem of the West),” the description of the body in an animalistic way in the poem “The Thing about Nature,” the last sentence about my father in the poem “Earth 地球 Mother 妈妈 Father 爸爸 Race 种族” that juggles the image of a phantom with a racist trope. All of that is accessible. All of that is representative.

Where I wanted a different kind of vividness was in depicting the brutality of California and the West for black people, for nature. I wanted to break the illusory image of the Golden State as this idyllic multicultural melting pot where progressive liberal attitudes floated on the wind and waves. So I opted to include two photographs in order to differently illustrate the totality, the finality, of black death and the clear cutting of redwood trees–one long genocide on a linear and nonlinear timeline–in this gorgeously, beautifully, abundant place. In some ways, photography is like poetry in that it tells a story succinctly, leaving it up to you to interpret the larger story with just the cues presented.

BUP: Do you have any overarching questions or challenges you would like to pose to a reader? something you would like them to ponder as they experience your poetry?

Thompson: Three big picture questions that I want my readers to ask themselves are: Where are your people from? What are some of the stories—the PR campaign, the hidden, the aspirational, the obscene, the mundane—that form your larger family narrative? And how does your own personal narrative fit into that story?

I want my readers to understand that this is how family histories, community histories, regional histories, national histories, get written: everybody has a version but not everyone’s version fits or is centered or even visible. I also want readers to think about the role objects, buildings, places, and time have shaped their sense of belonging. There are a number of objects, buildings, skylines, and landscapes that I hold up and examine in Black California Gold. One of my favorites is this absurd list of abstract things fictionally found in my compost bin in the poem, “Black Garden Songs.”

Finally, I want readers to consider the cost and relationality of things: profit, property ownership, generational wealth, gentrification, belonging. In order for each of us to experience and have comfort, peace, safety, security, leisure, power, authority, autonomy, sovereignty, there are others who are deliberately excluded and withheld from ever achieving, receiving, or possessing any of those things. We experience them at their expense. Our gains are predicated on their losses, which is, at the end of the day, not just a black story or California story, but a very American story.

Black California Gold is available to order here in paperback, hardback, and ebook.

Wendy M. Thompson is an Oakland native whose creative work has most recently appeared in Obsidian: Literature & Arts in the African Diaspora, Juked, and Hayden’s Ferry Review. She is an associate professor of African American studies at San José State University.