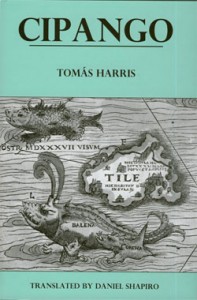

Daniel Shapiro is the translator of Cipango, published by Bucknell University Press in 2010. The book has received outstanding exposure, including a starred review in Library Journal, a review by translator Edith Grossman in The American Poetry Review, and additional coverage in publications including Hispamérica, The Quarterly Conversation, and World Literature Today. Shapiro is Director of Literature at the Americas Society in New York, and Editor of Review: Literature and Arts of the Americas. He is also the author of the poetry manuscript “The Red Handkerchief,” now seeking a publisher.

Daniel Shapiro is the translator of Cipango, published by Bucknell University Press in 2010. The book has received outstanding exposure, including a starred review in Library Journal, a review by translator Edith Grossman in The American Poetry Review, and additional coverage in publications including Hispamérica, The Quarterly Conversation, and World Literature Today. Shapiro is Director of Literature at the Americas Society in New York, and Editor of Review: Literature and Arts of the Americas. He is also the author of the poetry manuscript “The Red Handkerchief,” now seeking a publisher.

—————————————————————-

How did you first encounter Tomás Harris’s poetry and Cipango?

My first exposure to Tomás Harris’s work was through my position at the Americas Society. I was presenting a series of readings by Chilean authors in Fall 1993; Tomás was one in the group of participating writers, which also included poets Teresa Calderón and Jaime Quezada, novelists Jaime Collyer and Diamela Eltit, and various playwrights. Tomás, by the way, is an important contemporary voice in Chilean literature, a recipient of international awards including the Casa de las Américas prize, and, in Chile, the Pablo Neruda and Altazor awards. Anyway, I read his poetry collection Cipango and was immediately attracted to the poems. The book, it should be noted, was written in the 1980s, during the Pinochet dictatorship (1973-90) and first published in 1992 by Ediciones Documentas/Ediciones Cordillera; a second edition, published by Fondo de Cultura Económica, appeared in 1996.

What was it about the work that attracted you? Like many readers of poetry, I’ve long admired the Chilean poetic tradition, beginning with my exposure to Pablo Neruda and Vicente Huidobro. Tomás Harris’s work, while iconoclastic, is part of a long illustrious canon that includes those poets and others—Gabriela Mistral, Nicanor Parra, Gonzalo Rojas, to name a few. The first poem I read in Cipango, “Diario del terror encerrado en una botella”—which I translated as “Diary of Terror Sealed in a Bottle”—has a dark, obsessive, incantatory voice, as well as strange imagery and a powerful rhythm. It opens with the lines “Besides fog / in the ship’s hold there are boxes / boxes like factories filled with clay. . .” These elements are present throughout the collection. The poems also make use of irony, as well as juxtapose archaic and contemporary diction, and are infused with numerous literary and historical references (e.g., Genghis Khan, Columbus’s diaries, Dracula, Herman Melville, the Holocaust, Jean Genet, Billy Holiday, the film Goldfinger and local events and places in Chile, particularly in Concepción, where many of the poems are set). The collection functions as a long epic poem, a metaphorical journey, in effect, through Chilean, Latin American, and literary history. Thematically, it explores a violent, decadent, apocalyptic world that nonetheless contains the possibility for regeneration, where “the water of myths and dreams” can “stanch the purple stains from our bodies / with the cleanliness of a new human form,” to quote from the poem “Vacant Lot.” All of these qualities piqued my imagination and inspired me to translate the entire book.

What are some of the highlights in terms of your translation and publication of the collection? The process of translating Cipango and finding a publisher for it took me seventeen years. That long period allowed me to contemplate the poems individually and collectively and to fully realize my translation. During that time, I was submitting the poems to journals and the whole manuscript to publishers. In the summer of 1997, The American Poetry Review accepted a generous selection of my translations from the book, and showcased Tomás Harris as the cover feature of its September/October 1997 issue. Other publications in journals and culture publications followed—including in BOMB, Chelsea, Grand Street, Literal, and others. In 2003, I received a fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts to complete the translation, which allowed me to travel to Chile to work in person with Tomás as well as to further explore the country, including Concepción, where many of the poems are set. This trip enabled me to make important corrections on the translations and to compile a section of endnotes. Finally, in Fall 2007, Bucknell University Press accepted Cipango for publication and, last year, published it to acclaim.

Could you discuss the relationship of Cipango to Chilean and Latin American history?

Could you discuss the relationship of Cipango to Chilean and Latin American history?

As mentioned, the book draws on many sources from Colonial to contemporary times. Its main point of departure is Columbus’s arrival in the Americas, his mistaken premise—he thought he’d reached Asia/the East Indies (Cipango or Japan), not Hispaniola (present-day Haiti/Dominican Republic)—and the dark history that followed. This legacy serves as a metaphor for the violence and degradation in the Americas beginning in 1492 and which culminated, in Chile, with the Pinochet dictatorship (1973-1990). Because of the earthquake last year in Concepción and the rest of the country, the book has taken on an almost prophetic quality, and is also about Chile today. I want to underscore that while this book was written by a Chilean author and is set largely in a setting that draws on Chile, it is a universal work. This is made evident through its myriad references over time and place, its almost primal rhythm and use of other literary elements, and its suggestion of history as a reference point or compass. Finally, the book looks into the future by posing a question in the concluding poem (“Poeisis of the Better Life”): “What will happen after all this?”

What is the relevance of Cipango today?

Cipango reminds its readers of the inherent violence that has recurred throughout history, whether actual or dormant, generated by human beings, societies, governments, or nature (as in the case of the 2010 earthquake). It is an appeal for an understanding of the past, as well as for clarity, vigilance, and compassion when approaching the present and future. That goes for when we’re talking about the abuses of Colonialism and authoritarian regimes typified by the Pinochet era, as well as when we observe how people react, behave, and even speak and write during crises such as dictatorships and earthquakes. All in all, Cipango is a call for humanity on both individual and collective levels.

Are you working on any other books by Tomás Harris?

I’m currently translating his Historia personal del miedo (A Personal History of Fear; 1994), a collection of gothic horror stories à la Edgar Allan Poe; and Itaca (Ithaca; 2001), a poetry collection that uses, as points of departure, paintings such as Gericault’s Raft of the Medusa and films such as The Man With X-Ray Eyes and Blue Velvet. I’m thoroughly enjoying the process.

Are there any words you’d like to leave us with?

I’d like to underscore the imaginative power of the poems in Cipango, individually and collectively. As the author says in one of my favorites in the collection, “Beneath the Shadow of Limed Wall”: “And in the unabsolved delirium / where we all ended up, we began to imagine things.” That seems like an apt metaphor for the book and for the life of poetry.

The bilingual edition of Cipango is available online on the Bucknell University Press website as well as through Rowman and Littlefield and Amazon.com, in New York City, at McNally Jackson Books.

This is a kind of very studied art. Daniel Shapiro gave his soul,to readers. He studyied any comma, any point, any question mark to do this translation. This is something very well done, meticulous, minded details. Amazing poetry. As matter of fact, this is something …wonderful!!!