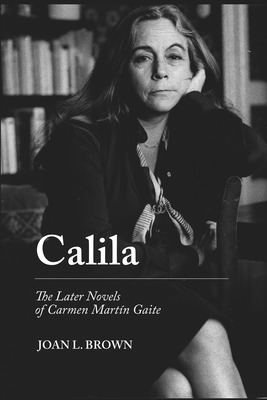

Spanish author Carmen Martín Gaite, Spain’s most honored contemporary woman writer, was recognized for her short novel El balneario [The Spa] with the Café Gijón Prize in 1954, won the Nadal Prize in 1957 for her second novel Entre visillos (Behind the Curtains), and earned Spain’s National Prize for Literature for her 1978 novel El cuarto de atrás (The Back Room). Her subsequent works of fiction—all bestsellers when they appeared—have received less critical attention. In Calila: The Later Novels of Carmen Martín Gaite, Joan L. Brown, until recently the Elias Ahuja Chair of Spanish at the University of Delaware, writes the first comprehensive study of the author’s last six novels. Brown contributes to current scholarship about the author, and also shares unpublished letters and conversations with Martín Gaite—a dear friend whom she called Calila. The book is enriched by the voice of the Spanish author herself, and elucidates themes in her work that remain relevant today.

Here we talk to Joan L. Brown about her relationship with Martín Gaite, personal and Spanish history, and female agency:

What impelled you to write about the later novels of Carmen Martín Gaite, Spain’s most honored contemporary woman writer and your dear friend? Why did you write the book now? How did your friendship affect your role as literary critic?

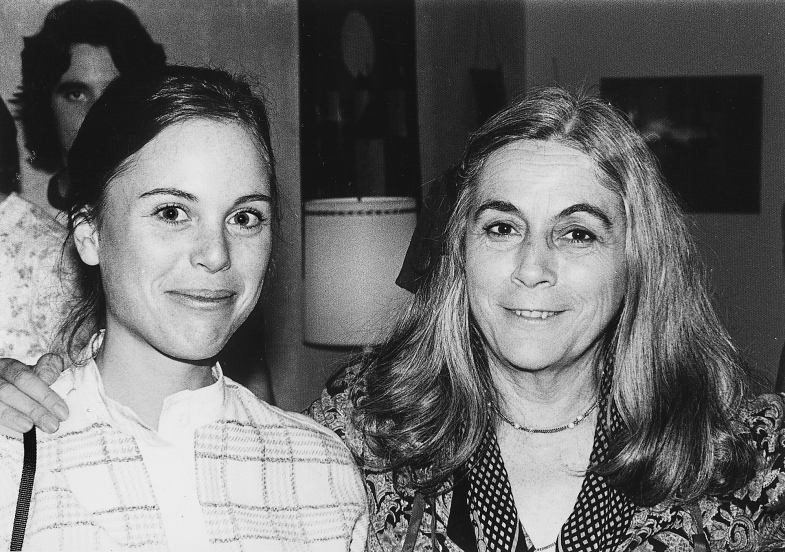

I’ve wanted to write this book ever since I realized that Martín Gaite’s last six novels had been somewhat overlooked by literary critics. This lack of appropriate recognition was the same reason I wrote my earlier book about her first five novels, though they had the opposite problem: many critical awards but few of them known outside Spain. In Spanish we have the word “reivindicación” which suggests calling out an injustice, and that was my driving force. The only problem was that I couldn’t write about these novels when they came out—I was too close to my friend, whom I called Calila, to be an objective critic. After twenty years I was able to gain distance and perspective.

In the book you trace two histories, the personal history of Carmen Martín Gaite and the sweeping history of democratic Spain. How do these histories intersect? What would a reader be surprised to learn about each one?

Spain’s history and the author’s history are inextricably intertwined. Her trajectory illustrates the maxim that historical events have more influence on a person’s life than his or her own decisions. Surprises come from pulling back the curtain on the rosy story of Spain’s transition from dictatorship to democracy and revealing the fallout for youth of that era. The transition had staggering societal costs, many of which were obscured by what was called the “pact of forgetting” that enabled former enemies to coexist. These costs were exceptionally high for young people, who were offered unlimited freedoms—the government turned a blind eye on drugs, some say cynically in order to silence rebellion—at a time when career opportunities were nonexistent. Carmen’s daughter Marta was a member of what is now known as Spain’s “lost generation.”

You observe that the six novels analyzed in Calila “explore themes that resonate today.” Please elaborate.

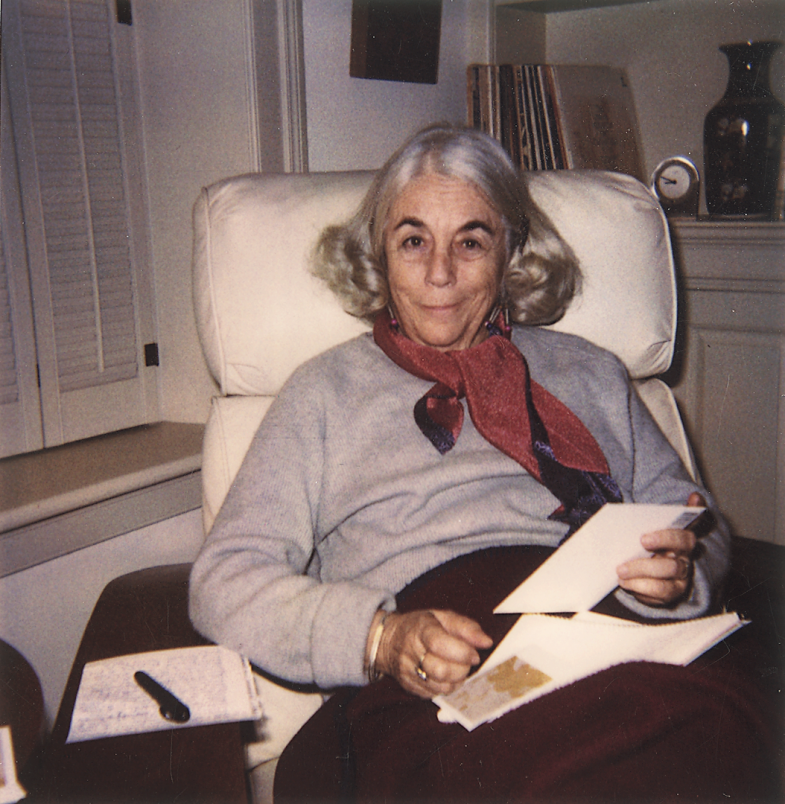

The themes explored in her last six novels could be taken from today’s headlines: women’s struggle for equality and self-actualization, the degradation of the earth’s environment, new configurations of family and friendship, the isolating effects of technology, the devastating impact of an uncontrolled plague. From the beginning of her career, Martín Gaite functioned as an anthropologist to her own culture. She had a sharp eye for human behavior and an even sharper understanding of human nature, though she was one of the least judgmental people on the planet. She was also supremely optimistic. A trained historian (with a doctorate from the University of Madrid), she viewed the past as a tool for improving the future.

How do Martín Gaite´s last six novels compare with her first five? What do you want readers to know about the two periods of her literary production, which were separated by a decade of sociocultural research?

Her first four novels in the 1950s and 1960s were written under censorship. They chronicled life for men and women under a dictatorship, using what author Juan Goytisolo described as “elusive-allusive” techniques—eluding the censors while alluding to social issues. Martín Gaite´s fifth novel, published in 1978 after censorship had ended, remains her most celebrated. El cuarto de atrás (The Back Room) is a unique hybrid—a fantastic novel that retrieves real memories of growing up female in Franco’s Spain. By the 1990s Martín Gaite could write whatever she pleased, and she let her imagination soar. From a young adult adventure set in New York City to an epistolary novel about two brave and talented Spanish women, to a fractured fairy tale that depicts Spain´s transition to democracy, to a Proustian memoir of mother-daughter love and conflict, to a tapestry of vignettes tracing a successful woman’s return to her birthplace, to a gripping story of a Spanish millennial striving to decipher his family’s secrets—her novels of the nineties would have been unimaginable earlier.

You write about “female agency” with regard to Nubosidad variable (Variable Cloud) and the epistolary genre. More generally, how is Martín Gaite’s work—including fiction and nonfiction—associated with agency and identity?

All of Martín Gaite’s writings are about human agency: male and female. She disliked artificial distinctions and roles, remarking in an interview that people should be free to just be as they are. In each of her novels of the nineties, characters work through issues of present-day identity by sorting through memories of the past—figuring out how they became who they are now in order to advance confidently into a brighter future. Just as her characters vanquish ghosts of the past—their own and Spain’s—Martín Gaite uses memory, language and writing to recover her own sense of agency after the death of her only child.

The book analyzes Martín Gaite’s later novels in their historical and critical contexts. Thanks to your connection to the author and your trove of letters from her, Calila also sheds light on the novels’ biographical context. What do you want readers to take away from this book?

I want them to go back and savor these extraordinary novels with heightened awareness of the author’s own story and the story of her times. Each novel is a unique gem. Martín Gaite felt that her first responsibility as an author was to build a bridge to the reader, and she succeeded in making her bridges so strong that they support even those who have no prior knowledge of the country on the other side. Critics have called Carmen Martín Gaite one of Spain’s two great prose stylists of the twentieth century, along with Miguel Delibes, and I want readers to see why. My goal is for readers to appreciate the second half of Martín Gaite’s literary output along with the first half, assuring her a place in the canon of contemporary Spanish literature.

Martín Gaite continues to be admired on both sides of the Atlantic—with celebrations planned for the centennial of her birth. Calila: The Later Novels of Carmen Martín Gaite is available for order in paperback, hardback, and ebook.

This is gorgeous, a fitting tribute to Carmiña —and to Dr. Brown.