Edna O’Brien’s work ignited controversy in Ireland and abroad ever since the publication of her first novel, The Country Girls, in 1960. Writing openly about the inner lives of girls, including their sexual experiences, O’Brien’s early works were banned by the Irish government and condemned by the Catholic church in Ireland.

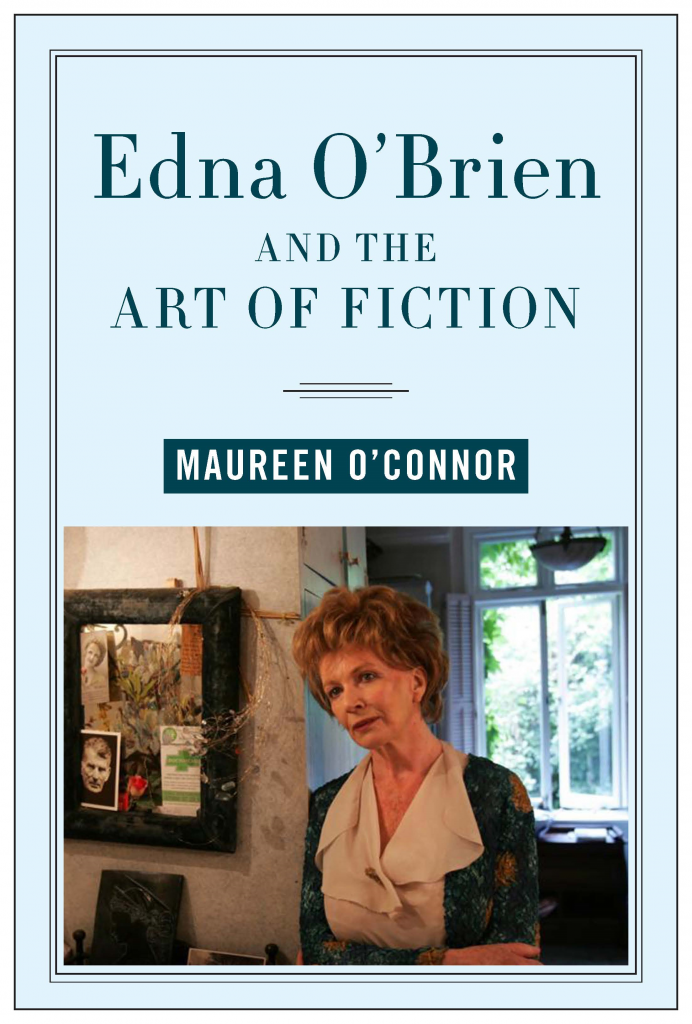

Since her debut novel, O’Brien has written over twenty works of fiction, along with biographies of James Joyce and Lord Byron, her own autobiography, plays and screenplays, as well as countless short stories. She has received many awards in Ireland and abroad including the Irish Pen Lifetime Achievement Award, the Ulysses Medal, the PEN/Nabokov award, and the French Commandeur de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres. She is widely regarded as Ireland’s greatest living writer. In Edna O’Brien and the Art of Fiction, Maureen O’Connor, lecturer in English at University College Cork, considers O’Brien’s fiction in the 21st century, applying new theoretical approaches to her work and examining her pioneering and enduring portrayals of women’s experience, relationships, the natural world, sex, creativity, and death. Published in Bucknell UP’s Contemporary Irish Writers series, this critical retrospective contributes to important reconsiderations of canonical and emerging authors.

Here we talk to Maureen O’Connor about themes in O’Brien’s work, her relationship with second-wave feminism, and her distinctly Irish embrace of the inanimate.

O’Brien includes women characters and storylines of maternity while making loss a primary theme. How do loss and maternity intersect in O’Brien’s work? How does this intersection reflect Irish national identity and “Mother Ireland”?

O’Brien has said from the early days of her writing career that loss was her “central theme,” and your question is perceptive in situating that sense of loss in the first relationship, that between mother and child. As she said to Shusha Guppy in 1984, “Loss is every child’s theme, because by necessity the child loses its other and its bearing.” The persistence and suffering of that original wound is compounded for the female child in O’Brien’s fiction when the mother is a defender and enforcer of the patriarchal structures, undergirded by Roman Catholic dogma in Ireland, that constrain and suppress women. The irreconcilable tension between feelings of love and betrayal that require a denunciation and rejection of the mother can be mapped onto a national trauma in O’Brien’s writing. As she said in the memoir / travelogue Mother Ireland, the connection between Ireland and its scattered children is “more umbilical than among any other race on earth.” The Irish psyche in O’Brien, for men as well as women, is rendered weak and cruel in its formation, dominated by a romanticised mother figure who is at the same time denigrated and marginalised.

There is a significant investment in the “mother” figure within O’Brien’s work. In your analysis of O’Brien’s The High Road, you write that Anna “is a version of O’Brien’s Irish ‘mother,’ complicit in maintaining the patriarchal hierarchies” (32). Is it possible for Irish women to resist the system when being held to an “impossible model offered by the Virgin Mary” (25)?

As mentioned above, the mother figure is a deeply paradoxical one in O’Brien’s fiction, completely adored and yet necessary to escape in order to survive. The limited range of power and influence available to a “good” Irish woman of O’Brien’s childhood was confined to the domestic sphere, where the mother was both tyrant and slave, not only to other members of the family but to herself as well. Even the women of O’Brien’s generation who fled the family, the religion, and even the country of their birth, seemed doomed to be failed mothers. In the novels and short stories, O’Brien’s young mothers are largely neglectful, with sometimes fatal results. Without a model of healthy, nurturing maternity to draw on, her young mothers, usually simultaneously pressured by the emerging culture of self-actualisation and sexual liberation, struggle to balance their own needs and their parental responsibilities. While women might blame themselves, O’Brien’s’ fiction places the blame for the almost-inevitable damage that emerges from Western models of maternity on the dysfunctional nuclear family.

O’Brien processes emotional damage that has “led her to a distrust of her own body,” which arises within her texts (25). The discussion of womanhood, motherhood, and women’s’ relationships with their bodies are often considered forms of feminist practice. Do you consider Edna O’Brien a feminist author? How might this contrast with O’Brien’s hesitant opinions concerning the second-wave feminist movement?

I am not the only critic who would confidently identify Edna’s fiction as feminist praxis, whether or not she is comfortable with the label herself. Feminist critics were the first to take her work seriously as an appropriate subject of scholarly attention in the late 1990s. We are now well aware of the ideological structures and limitations that attended the dominant strains of second-wave feminism, which failed to make cause with working class or bisexual and lesbian women, for example. Some of the most scathing and condemnatory criticisms of O’Brien styled themselves as feminist critiques, another example of betrayal by those for whom she is, arguably, writing what Julia O’Faolain called in 1974 “field reports on the feminine condition at its most acute,” for which “feminists should be grateful.” O’Brien’s treatment at the hands of feminist commentators in the early decades of her career provides an example of another of her central themes, one she shares with her literary idol, James Joyce, and noted above in reference to the mother-daughter relationship: betrayal. An expert in irony, O’Brien has long understood the deep roots of misogyny, even amongst women ostensibly dedicated to battling it.

How does O’Brien balance the liveliness she gives to the inanimate while tapping into “the primal dread at the heart of folk and fairy lore” (85)?

O’Brien’s great care with and attention to physical detail is a quality that even her most dedicated detractors recognise as a strength in her writing. Nonhuman objects are as at least as loveable and precious—maybe more so—than many of the human characters in her fiction. O’Brien grew up in a rural landscape alive with fairy lore and mythology. As recently as 1999, the construction of a motorway in County Clare (where O’Brien was born and grew up) was halted and the plans changed to avoid the destruction of a fairy tree. This is the same country where, in the summer of 1985, statues of the Virgin Mary around the country, but especially in the Cork village of Ballinspittle, were reported to be moving. The distinction between the animate and the inanimate, between the living and the dead, is not well defined or fixed in an Irish context. That such distinctions are not reliable can be liberating as well as terrifying, and in that space of danger, uncertainty, and fear is where O’Brien locates the source of creativity. She has described herself as a very fearful person, but only the fearful can be truly brave.

What do you want readers to take away from this book?

Above all, I want readers to come away from this book inspired by the example of O’Brien, a woman who grew up in straitened and oppressive conditions, who never attended college, but who nevertheless became one of the best-selling writers in the English language, who is regularly the recipient of international awards for the widely-acclaimed quality of her writing, and who has defended the rights of those most in need of protection all through her career, in her writing as well as in her personal advocacy.

For additional information, or to order Edna O’Brien and the Art of Fiction, please click here.

Interested in the Contemporary Irish Writers series? Click here to read an interview with series editor, Anne Fogarty.