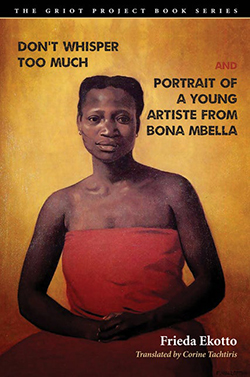

Frieda Ekotto is a professor of comparative literature at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and currently serves as the chair of the department of Afroamerican and African studies. Her early work involves an interdisciplinary exploration of the interactions among philosophy, law, literature, and African cinema. Don’t Whisper Too Much was first published by French publishing house L’Harmattan in 2005, and was translated by Corine Tachtiris to make Don’t Whisper Too Much and Portrait of A Young Artiste from Bona Mbella, published by Bucknell University Press in 2019. In February, I was allowed the privilege to ask Professor Ekotto a few of my own questions about her stunning works.

How do you begin a new work? What is your process for beginning a new project?

I would like to write all the time but it is impossible because of my work as a professor.

Writing fiction is my solace. It really helps me on a daily basis. It is like reading. If I do not read a piece of a story every day, I feel like the world is empty. I have so many ideas, I want to put them down. Therefore, as soon as I have a little bit of time, I articulate an idea in order to come back to it for either a short story or a novel. Writing fiction allows my imagination to fly all around me.

These works were first published in French, and you’ve stated before that the publishing process for Don’t Whisper Too Much had its challenges. What was that like, and what is your take on how the publishing industry should intersect with the lives and stories of underrepresented groups?

In the novel Don’t Whisper Too Much, I really wanted to talk about love between women. How women can love each other. It is difficult to talk about love. We usually talk about stories on love and sacrifice in a visual poetry full of sensuality and emotion. Aesthetically, I wanted to focus on the bodies, the loving body as such: the two main characters Affi and Siliki work on the different movement of the body, disabled body that moves very slowly, dreaming, thinking, loving, speaking and body escaping confinement of sexual body. This will allow me to work on the new framing of presenting the African female body: a different gaze, an African gaze as well as an aesthetic on slowness of the way these bodies move. These two main characters move slowly with the focus on the face, on specific parts of the body, faces, eyes, private parts. In a closed door I wanted to show intimacy as well as spaces of resistances, an opening to escape confinement as well as conditions of possible freedom, which symbolize the openness, alterity and mostly tolerance. Aesthetically, I seek to invent a writing form to allow openness, possibilities, and forms of breathing necessary for freedom to be. In other words, create a narrative that renders plausible form of objectivity, a poetic message, something purely fictional that would affect souls. Don’t Whisper Too Much traverses different life stories and histories, trajectories dealing with time and feelings of issues fear and desire. The characters Affi and Siliki’s stories relate to suffering of many women as well as other humans with alternative voices.

Have the responses from your English readers differed in any way from your original audience?

Yes. There is a tradition within the Anglo-Saxon world of already well-established homosexual writers. Here my inspiration is James Baldwin. His work is about love and this is what I want to reproduce within the continent of Africa. The translator of this work wrote an excellent article on the process of translating my work. See: Corine Tachtiris “Giving Voice: Translating Speech and Silence in Frieda Ekotto’s Don’t Whisper Too Much.” This piece is useful for teaching. My work is important because it is a different voice, a voice coming from another space. In general, readers love to discover voices from far away like those coming from Africa. Our continent is a huge one with diversity of cultures and languages, therefore, I want to add my voice to the multiple voices defining ourselves, writing ourselves and our stories in world literature.

Why choose to have Don’t Whisper Too Much and Portrait of a Young Artiste from Bona Mbella together in a single volume? How do they speak to one another?

Don’t Whisper Too Much is remarkable not just for being arguably the first African novel to deal frankly with women who love women but also in that it is very “non-confrontational” for a general African audience. There is a lot of love, intimacy, and desire, but nothing that could be called pornographic or even overtly sexual. This was a conscious decision to gain traction with a wider, even more conservative audience. In these two novels, there is a stylistic continuation of what I can do in my work, a specific desire to take a different approach to representing women who love women in an African context. In any case, I think the content of these short stories and their raw power are completely different from the first novel. Yes, my ideas are inflammatory because I want readers to note that this is a different world.

Within the first few pages of Don’t Whisper Too Much, you write that “Silence permeates every relationship.” In the introduction of Don’t Whisper Too Much, Lindsey Green-Simms claims that “Writing, then, allows Ekotto to carve out spaces within this confinement to ‘pierce the imperceptible layer of the unsayable and slide through the cracks.’” What does this mean for you? How does silence affect your work?

As a postcolonial subject, silence is part of how we are in the world. My desire is to write in my mother’s tongue, but this is impossible, so I translate part of what I cannot say into silence. My major question is how to translate Other’s silence. It is important for me that the voices of ‘Others’ be heard and not silenced by being squeezed into or ignored by so many dominant discourses or what Jean François Lyotard called “master narrative.” This means that our attempts to “explore the ‘Other’ point of view” and “to give it a chance to speak for itself” must always be distinguished from the other’s struggles. In my case, this means that I speak from the position of a postcolonial subject and that my speech can be localized within the postcolonial context despite the logical inconsistencies propelling it. I also know, however, that it is necessary for me to first master my own language before attempting to appropriate the master’s discursive control over language. Derrida discusses the question of the other’s language in Racism’s Last Word, pointing out that one must master how to “speak the other’s language without renouncing [our] own.” In other words, translating silence is like facing ‘a wall,’ therefore to speak or to learn how to speak means to find a hole and then the wall will tumble. In fact, I am only reminding Africans that it is about time to learn how to speak, to find a hole for themselves, for their history to be heard. I am quite aware of the cultural implications for a silenced voice who seeks “to learn to speak to (rather than listen to or speak for)” in this particular global context. But what is crucial to understand here is not that the silence cannot be translated, but instead, that we include the necessary conditions for its translation not to be “only” localizable in the same margins of its contestation of liminality and exclusion. Translating silence is also reformulating agency that not only resists, but one that traces the teleologies of an alternative, a kind of new culture. It is within this space that I can speak of how translation of silence engenders the inscription of my subjectivity. It is also not necessary to translate silence all the time because it is the condition for so many people. Silence protects me and I am always careful how I want to uncover it.

If readers were to take one thing away from your work, what would you want that to be?

I would be very happy if readers understood the humanity of my characters who are dealing with same-sex love. To tell a story is a creative component of human experience.

I strongly believe that literature or other forms of creativity can help change attitudes in the continent of Africa on queer identities. Same-sex desire and sexual relationships between women in Africa have received scant attention in critical and cultural studies. Thus it is extremely important that we examine how homosexuality is used as a discursive tool, both in Africa and in the West that affects lives. Films and literary texts shape ethical reflection and cultural norms. I think it is extremely important to engage these materials, both to create new language and to expand our understanding of homosexuality beyond its current Western-oriented discourse. These cultural productions encourage and support women who love women to live in relationships of love, without fear of being killed, ostracized, disowned, or beaten.

We need more writing and other art forms on homosexuality in the continent. The more we talk about it, show images, sing songs or music, produce paintings, etc. we encourage more people to see that it is about showing homosexuals as humans. Since I am speaking out as a woman who loves women, I consider myself a dissident in the continent. Again, my approach to the question of dissidence in Africa engages not only different ways of being female, but also different ways of being queer.