To kick off the 10th annual University Press Week (UP Week) celebration, we invited author Manu Samriti Chander to share his thoughts on publishing with university presses and why they matter. Professor Chander’s first book, Brown Romantics: Poetry and Nationalism in the Global Nineteenth Century, published by Bucknell UP in 2017, calls for the academy in general and scholars of European Romanticism to acknowledge the extensive international impact of Romantic poetry. Reviewers agree, proclaiming it “the kind of book that Romantic literary studies has needed for a very long time”[1] and declaring, “[t]here’s no doubt that it will be looked back upon as a landmark work in Romantic studies.”[2]

“‘Leo’s’ poems have not even the thinnest guise of poetry. They illustrate a strain of trite, and often silly reflection, and a sentiment of ‘goodiness’ that is nauseating.” That was one London reviewer’s assessment of a poetry collection called Leo’s Poetical Works, which was published in 1883. The author in question, “Leo,” was an Afro-Guianese poet and essayist whose birth name was Egbert Martin. The review, which appeared in the Saturday Review on May 3, 1884, made its way across the Atlantic and back to Martin, who, understandably, took offense, writing in the preface to his second collection, Leo’s Local Lyrics, “Some…held that my book of poems published in 1883 contained too much ‘goody-goodiness,’ and I must confess that I have deliberately searched through at least two dictionaries without being able to discover such a word.” In a world in which an English reviewer’s opinion would always trump that of a Black colonial subject, Martin nevertheless found a way to express his frustration with the imperial order of things.

I learned of Martin’s poetry while conducting research for my first book, Brown Romantics, which looked at the way that colonial writers in the nineteenth century struggled to be considered as what Emerson (whom Martin had read and admired) called a “representative man”: “a monarch who gives a constitution to his people; a pontiff who preaches the equality of souls and releases his servants from their barbarous homages; an emperor who can spare his empire.” Or, in the case of the Brown Romantics, a poet capable of unifying diverse readers into a coherent whole. Martin, along with such figures as Henry Derozio in India and Henry Lawson in Australia, saw poetry as a means of community-building, a way of forging connections among peoples through the shared experience of reading. My book sought to recognize these figures in a way that reviewers from centers of literary power rarely did.

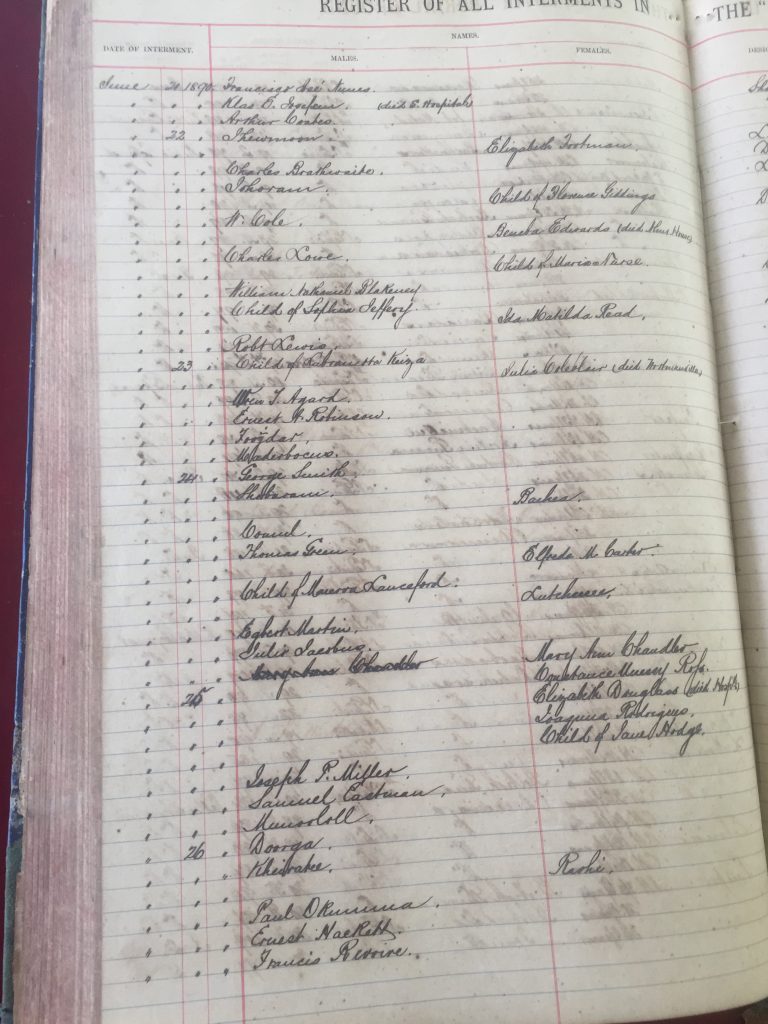

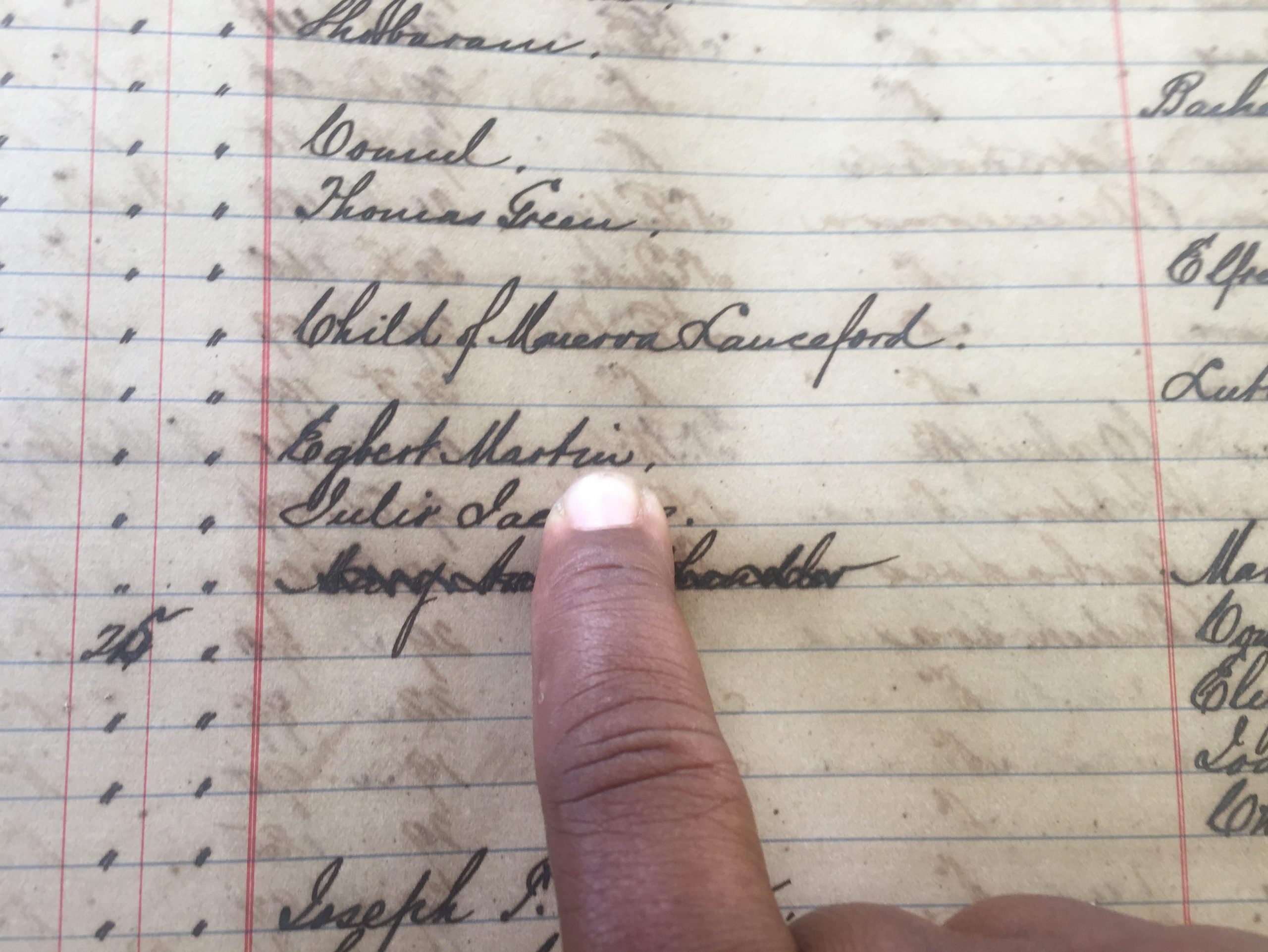

Shortly after the publication of Brown Romantics, as I was preparing an edition of Martin’s collected works, I visited Le Repentir Cemetery in Georgetown, Guyana, where, I knew from my research, Martin was buried. When I arrived at the cemetery office I was met by a woman who had never heard of the poet. She asked me to write down his information, name and date of death: “Egbert Martin,” I wrote, “June 24, 1890.” Just wait, she told me, and she headed to a back room, returning after several minutes with a large log book. When she found the page for June 1890, my heart sped up, and it continued to race as she ran her finger down the yellowed page. It landed on Martin’s name, penciled in neat cursive. Age: 29. Nation: Demerara. The log indicated where he was buried by division (New General), space number (30), and grave number (108). I asked if I could visit the spot, and I was told it’s a “mud grave,” no marker, nothing to see.

“Pecuniary success,” wrote Martin in the preface to Leo’s Poetical Works, “is…outside the Author’s anticipations; and fame, the idol of so many, for him has so little attraction that he cares not so much as to couple his name with his works.” And yet, we know from his response to his London critic, he was not without pride. I wonder what it might have meant to him to know that, over a one-hundred twenty years later, someone would see in his poetry something more than “trite” and “silly” “goodiness.” I wonder what it might have meant to him, as he labored daily over his verse, a “confirmed invalid,” as one British Guianese newspaper described him, largely confined to his home at 317 East Street in Georgetown (this, at least, is the address listed in an issue of the London periodical Truth on January 6, 1887)–I wonder what it might have meant for him to know that someone would one day see in the poems he wrote a serious contribution to that literary movement we call “Romanticism,” worthy of collecting and making available to readers across the globe.

Poetry is not as popular as it was in Martin’s time (although it is making a bit of a comeback). It is not regularly published in daily newspapers for readers to peruse casually as they get caught up on the events of the day. Nor is the study of poetry the stuff of popular books, not usually at least. It is largely sustained by scholars and, importantly, publishers who see value in poetic labor, both the labor of producing poetry and that of thinking through poetry in prose. Beyond–to recall Martin’s phrase–“pecuniary success,” we believe that something is gained, that the world is somehow better when we reserve a space for the analysis of line breaks and metrical substitutions, textual variations and publication histories. Perhaps that belief makes us Romantics, as well. If so–if we who publish with and work for university presses are inheritors of certain Romantic commitments–we have figures such as Martin to thank for sustaining these commitments, and for reminding us to sustain them as well.

Manu Samriti Chander is an associate professor of English at Rutgers University-Newark and the author of Brown Romantics: Poetry and Nationalism in the Global Nineteenth Century (Bucknell UP, 2017). He is currently editing The Collected Works of Egbert Martin (Oxford UP) and The Cambridge Companion to Romanticism and Race (Cambridge UP) and writing a second monograph, Browntology, under contract with SUNY Press.

[1] “Manu Samriti Chander’s Brown Romantics: Poetry and Nationalism in the Global Nineteenth Century is the kind of book that Romantic literary studies has needed for a very long time. Brown Romantics examines how and why poets from India, Guyana, and Australia placed themselves into conversation with authors now commonly associated with British Romanticism. The book significantly expands our understanding of canonical Romanticism’s transnational reach and revises critical commonplaces that have defined Romantic aesthetics since the nineteenth century.”

— Papers on Language and Literature

[2] “This book has already provided a focal point for a new direction in Romantic studies, as emerging research clusters around its central claims. There’s no doubt that it will be looked back upon as a landmark work in Romantic studies.”

— Romantic Circles