Guest blogger Jason S. Farr, of Marquette University, concludes University Press Week with his profound and personal post on disability and perception.

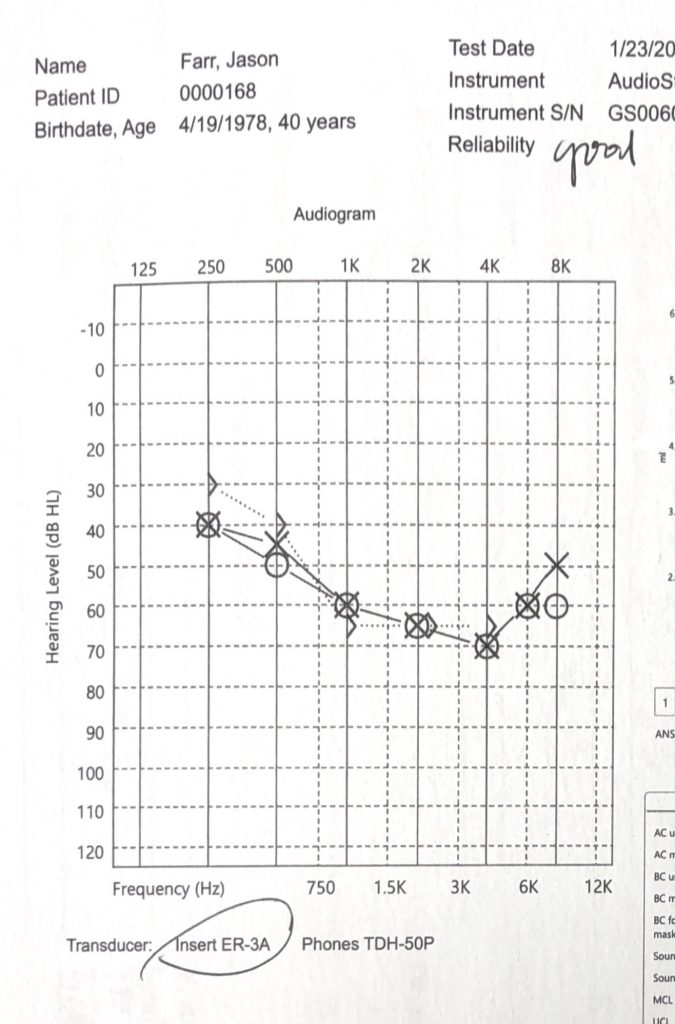

When I was 29, I suddenly found myself struggling to hear professors speak in the graduate seminars I attended. Conversations with friends and classmates became minefields of misunderstanding and sources of frustration. My physician referred me to an audiologist for a hearing test. She sat me in a dark booth and placed heavy headphones over my ears. Alone and filled with anxiety, I went on to fail an impossible test: somewhat discernible beeps followed by faint beeps followed by silence and the ringing oblivion of my tinnitus. The audiologist showed me the exam’s results, a line graph which plummeted at the mid-to-high frequencies. The diagnosis shocked me: I was severely hearing impaired.

The audiologist advised me to purchase behind-the-ear hearing aids but I opted for the completely-in-canal ones because they were less visible. They would require more repairs and would be uncomfortable to wear, she warned me, but I was ashamed. To have a visible indication of diminished capacity was unthinkable to me at the time. In retrospect, I wasn’t just confronting profound cognitive disorientation due to the mechanized, digital soundscapes I was learning to process; I was reconciling myself to how people reacted when they noticed the hearing aids themselves. The question that I came to dread in casual conversation was “what happened to you?” which may as well have been, “what’s wrong with you? Why aren’t you able-bodied?” For a young man navigating the body-driven subculture of gay San Diego, hearing aids called attention to my disability, and disability was something I regarded as compromising the body I was building in the gym and on basketball courts. Coming out as gay seven years prior to all of this was grueling, but coming out as disabled offered an entirely new set of challenges. In many ways, claiming my disability was even more difficult than claiming my gayness because of how deeply embedded and unchecked ableism is in our social and medical systems.

In the face of all this, I continued through the PhD program in Literature at UC San Diego where I would soon become acquainted with disability studies. One of my professors, Michael Davidson, introduced me to this vibrant interdisciplinary field and, consequently, to new ways of thinking about myself and others. In disability studies, for instance, disability is conceived of as a social and cultural phenomenon, not merely a physical one. Disabled people are often regarded as defective. But by reading disability activists and scholars, I soon learned that disabled people are manifestations of biological and cultural diversity, impaired perhaps in our bodies and minds but ultimately constrained by the communities we navigate, by the systems of thought to which we are exposed, and even by language itself, which reinforces ableism with clichéd metaphors of blindness-as-ignorance, of deafness-as-obtuseness, and of crippling-as-inhibiting.

When it came time for me to write my dissertation, I turned to disability studies to help me understand how literature reimagines social and political structures. I began by writing about Sarah Scott’s Millenium Hall, published in 1762. Scott’s utopian novel depicts a British country estate run by variably-embodied women whose utter abhorrence of heterosexuality and patriarchy is matched in intensity only by their boundless love for each other. Curiously, all of the servants of the estate, and the inhabitants that live within the estate’s walls, are what we would today call disabled—deaf, blind, maimed, short-statured, neuroatypical, and so on. What I eventually realized was that, in writing queer and disabled bodies into her narrative, Scott imagines a social order that remedies the wrongs of her day. In Scott’s utopian reckoning, variable bodies and queer intimacy work together to reform a society that prizes freak shows and treats women as property.

The book that eventually came out of my dissertation and which was recently published with Bucknell University Press, Novel Bodies: Disability and Sexuality in Eighteenth-Century British Literature, is the culmination of years of research and rewriting. It argues that Scott’s novel and other fictional narratives from the eighteenth century reveal the extent to which ableism and homophobia govern social life, but it also shows that, through the disabled and queer bodies that they imagine, authors opened up new avenues of lived experience for readers from the eighteenth century forward.

Much like the fictional characters in the novels I write about, becoming disabled has enabled me to perceive myself and the world differently. It helps me to discern more acutely the plights of the people who compose the communities I inhabit. It spurs me to try to improve these communities in my own imperfect and limited ways. I don’t want to downplay the exhaustion I feel at the end of classes and office hours, after listening as attentively as possible to the ideas, questions, and concerns of students and colleagues. But I’m also motivated and energized by my impairment. Like the fictional characters of eighteenth-century novels, my body is novel, it is extraordinary, and it is rewriting the script that was designed for me. My hearing is unwieldy, to be sure, but it is also directing me toward new social landscapes whose expansive vistas I am only just beginning to perceive.