Happy Women’s History Month! To celebrate, Bucknell University Press would like to share a few words from Misty Krueger, editor of Transatlantic Women Travelers, 1688-1843, followed by some of our own reading recommendations for learning about women’s lives throughout history.

Transatlantic Women Travelers is an important new collection that brings fresh perspectives on representations of late seventeenth- through mid-nineteenth-century transatlantic women travelers across a range of historical and literary works. While at one time transatlantic studies concentrated predominantly on men’s travels, this volume highlights the resilience of women who ventured voluntarily and by force across the Atlantic—some seeking mobility, adventure, knowledge, wealth, and freedom, and others surviving subjugation, capture, and enslavement.

Here’s more from our conversation with Misty Krueger:

BUP: Where did the inspiration for Transatlantic Women Travelers, 1688-1843 come from? Why is the woman’s experience of transatlantic travels in particular an important area of study?

Krueger: Transatlantic Women Travelers, 1688-1843 was initially inspired by a course I designed in 2015 for the University of Maine at Farmington called “Transatlantic 18th-Century Women.” I focused on the lives and writings of and about (mostly) British and American women who traveled transatlantically during the “long” eighteenth century. After teaching the course two times and helping students find research for their essays, I realized that there was plenty of scholarship on transatlantic travel from this time period, but that almost all of it focused on male travelers. When female travelers were mentioned, they often appeared as characters written by male writers. The focus seemed to be placed on men, and women appeared to be on the fringes, or in the male gaze, even though my teaching was showing me that there were plenty of women writers who traveled transatlantically and wrote about either their own travels or fictionalized women’s transatlantic travels. On top of that, these women were amazing! The hardships most endured and the advantages some gained were impressive, to say the least, so why wasn’t there a monograph or collection of essays dedicated to transatlantic women’s travel, I asked. One day in class I said—half joking, half serious—maybe I should edit a collection on this topic.

I proposed a call for papers for a special Aphra Behn Society panel at the American Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies conference to see what kind of interest the call might generate, and I received more submissions than I could accommodate for the session. Not long afterwards I wrote a call for papers and contacted Bucknell University Press. I knew that this collection would be perfect for Bucknell because of its Transits series and its excellent reputation for publishing some of the best scholarly work in eighteenth-century studies.

BUP: Could you speak to intersectionality in the collection?

Krueger: One of the things I hoped to find when I received submissions from the call for papers was variety: variety of travelers, authors, texts, and nationalities. I hoped to be able to bring together eighteenth- and nineteenth-century authors from around the Atlantic Ocean, as well as to bring together scholars from different points on the Atlantic. In the end, this collection features women travelers from Africa, Europe, and all of the Americas, as well as the Caribbean. Scholars hail from Canada, England, and the U.S.

I also hoped to put together a collection that would be intersectional in its broader representation of long eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century women’s lives. It was important to show the ways women’s lived experiences depended on not only their points of embarkation and arrival, but also the many facets of their identities. I was excited to receive essays addressing race, gender, sexuality, and class as composite factors that determine the advantages, disadvantages, privileges, and discrimination, Black, white, and multiracial women faced in this time period and why it is important to examine their narratives from an intersectional perspective. A number of essays demonstrate how these factors shape women’s lives, as well as the interconnected nature of women’s networks.

In the end, this volume collects the writings of amazing women scholars, including the fantastic Eve Tavor Bannet, who wrote the afterword, and focuses on a variety of women’s lives and writings.

BUP: From your own research or in editing the collection of essays, what is something new or surprising about these women and their narratives that sticks with you?

Krueger: I have been thinking about the women featured in this collection for so long now that this question is difficult to answer. I could say it’s their adaptability, but that’s not new or surprising to me. I could say it’s their mobility, but again not new or surprising. I could say it’s their sense of solidarity, even despite the social forces that pull them apart and tear them down, but that does not surprise me either. Instead, I want to focus on what sticks with me: their resilience. This is what amazes me most—just how resilient they were and still are. Transatlantic women travelers crossed the ocean for a range of reasons, some of which had to do with charting a new life and escaping the past, and many of which were decided by others, especially in the case of enslaved women and women forced to leave their homelands due to patriarchal directives.

Simply put, crossing the Atlantic Ocean from the eighteenth through the early nineteenth century was dangerous. To survive this journey, for some more than once in a roundtrip and some in the cargo hold of a slave ship, was no small feat. To survive this journey as a woman is even more spectacular. I am in awe of how the historical women featured in this collection managed this travel by sea and then land, and how writers of this era found ways to fictionalize women’s transatlantic journeys in order to make compelling arguments about women’s lives and their functions in their respective societies. This collection is dear to my heart because it reflects women’s strength and ability to persevere through the toughest times.

For more work on women’s history and lives, check out these other books from Bucknell University Press.

Intelligent Souls?: Feminist Orientalism in Eighteenth-Century English Literature

Intelligent Souls? offers a new understanding of Islam in eighteenth-century Britain. Cahill explores two overlapping strands of thinking about women and Islam, which produce the phenomenon of “feminist orientalism.” One strand describes seventeenth-century ideas about the nature of the soul used to denigrate religio-political opponents. A second tracks the transference of these ideas to Islam during the Glorious Revolution and the Trinitarian controversy of the 1690s. Rowe, Carter, Lennox, More, and Wollstonecraft, Cahill argues, established common ground with men by leveraging the “otherness” identified with Islam to dispute British culture’s assumption that British women were lacking in intelligence, selfhood, or professional abilities.

Don’t Whisper Too Much and Portrait of a Young Artiste from Bona Mbella

Don’t Whisper Too Much was the first work of fiction by an African writer to present love stories between African women in a positive light. Bona Mbella is the second. In presenting the emotional and romantic lives of gay, African women, Ekotto comments upon larger issues that affect these women, including Africa as a post-colonial space, the circulation of knowledge, and the question of who writes history. In recounting the beauty and complexity of relationships between women who love women, Ekotto inscribes these stories within African history, both past and present.

Jane Austen and Comedy

Edited by Erin M. Goss

Jane Austen and Comedy takes for granted two related notions. First, Jane Austen’s books are funny; they induce laughter, and that laughter is worth attending to for a variety of reasons. Second, Jane Austen’s books are comedies, understandable both through the generic form that ends in marriage after the potential hilarity of romantic adversity and through a more general promise of wish fulfillment. In bringing together Austen and comedy, which are both often dismissed as superfluous or irrelevant to a contemporary world, this collection of essays directs attention to the ways we laugh, the ways that Austen may make us do so, and the ways that our laughter is conditioned by the form in which Austen writes: comedy.

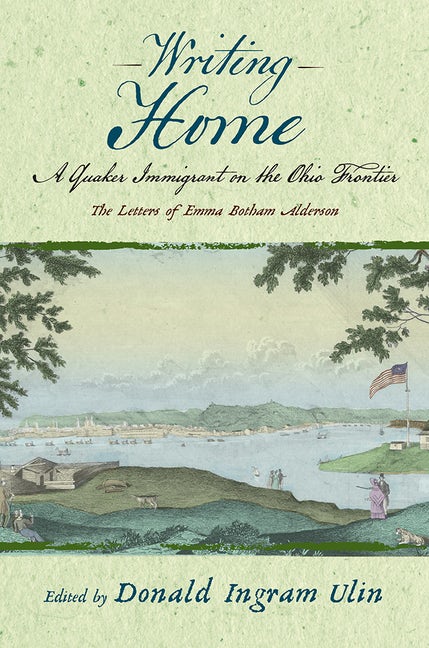

Writing Home: A Quaker Immigrant on the Ohio Frontier

by Emma Alderson, edited by Donald Ingram Ulin

Writing Home offers readers a firsthand account of the life of Emma Alderson, an otherwise unexceptional English immigrant on the Ohio frontier in mid-nineteenth-century America, who documented the five years preceding her death with astonishing detail and insight. Her convictions as a Quaker offer unique perspectives on racism, slavery, and abolition; the impending war with Mexico; presidential elections; various religious and utopian movements; and the practices of everyday life in a young country. Introductions and notes situate the letters in relation to their critical, biographical, literary, and historical contexts.

Modern Spanish Women as Agents of Change: Essays in Honor of Maryellen Bieder

Edited by Jennifer Smith

This volume brings together cutting-edge research on modern Spanish women as writers, activists, and embodiments of cultural change, and simultaneously honors Maryellen Bieder’s invaluable scholarly contribution to the field. The essays are innovative in their consideration of lesser-known women writers, focus on women as political activists, and use of post-colonialism, queer theory, and spatial theory to examine the period from the Enlightenment until World War II. Canonical authors such as Emilia Pardo Bazán, Leopoldo Alas “Clarín,” and Carmen de Burgos are considered alongside lesser known writers and activists such as María Rosa Gálvez, Sofía Tartilán, and Caterina Albert i Paradís.